So I was catching up on On the Media this morning, and heard this bit buried in a piece on the movement of public opinion toward approval of gay marriage.

… if we look back at interracial marriage, it was initially only at a 19 percent support level in 1968, one year after the Supreme Court, the U.S. Supreme Court, had acted in this issue.

19%! 1968! That seems crazy to me (I was in college at the time); 1968 is only yesterday, isn’t it?

On the other hand, 41 years seemed like a lot longer back then; in 1968 that would have been 1927, which, of course, is ancient history, right?

It has been said of predicting technological progress that we tend to overestimate advances in the short term and underestimate them in the long. That seems right to me, and the cases seems somewhat similar. Year to year, change happens at a glacial pace. Yet glaciers do move.

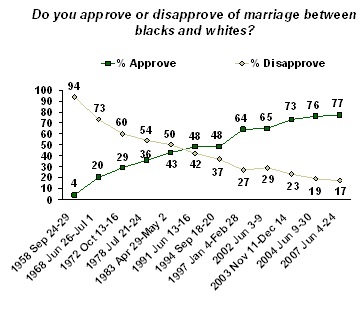

Having written the above, I did a quick search on the subject of public attitude toward interracial marriage. Here’s what Gallup finds:

Notice that there wasn’t even a plurality supporting interracial marriage until 1991 (now that is just yesterday).

I didn’t find such a concise presentation on same-sex marriage, and the data are harder to compare, since polls have been talking about both marriage and civil unions. But there’s a pretty good overview here. Two trends jump out at me. One is that opposition, especially strong opposition, to gay marriage is steadily dropping. The other is a dramatic age difference; one poll in 2008 found 69–22% opposition for gay marriage by respondents over 65, but 51–40% support by those 18–34.

In Anne Lamott’s words, “In a hundred years? — all new people!”

To be hopeful in bad times is not just foolishly romantic. It is based on the fact that human history is a history not only of cruelty, but also of compassion, sacrifice, courage, kindness.

To be hopeful in bad times is not just foolishly romantic. It is based on the fact that human history is a history not only of cruelty, but also of compassion, sacrifice, courage, kindness. As I was listening to a friend discuss the early days of digital computer design, and how much things had changed, it struck me that there is one common technology of similar age that would be instantly recognizable to its inventor: the Edison incandescent light bulb.

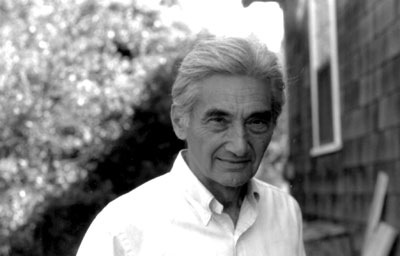

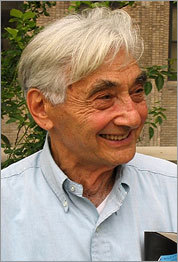

As I was listening to a friend discuss the early days of digital computer design, and how much things had changed, it struck me that there is one common technology of similar age that would be instantly recognizable to its inventor: the Edison incandescent light bulb.  Howard Zinn, the Boston University historian and political activist who was an early opponent of US involvement in Vietnam and whose books, such as “A People’s History of the United States,” inspired young and old to rethink the way textbooks present the American experience, died today in Santa Monica, Calif, where he was traveling. He was 87.

Howard Zinn, the Boston University historian and political activist who was an early opponent of US involvement in Vietnam and whose books, such as “A People’s History of the United States,” inspired young and old to rethink the way textbooks present the American experience, died today in Santa Monica, Calif, where he was traveling. He was 87. I noticed that I haven’t mentioned Lars Brownworth excellent lecture series,

I noticed that I haven’t mentioned Lars Brownworth excellent lecture series,

New software has enabled researchers to recreate a long forgotten musical instrument called the Lituus.

New software has enabled researchers to recreate a long forgotten musical instrument called the Lituus.