More to the previous point. This is Stephen Gandel, writing for The Curious Capitalist at TIME.com.

Paul Krugman’s War on Austerity

At a time when most people are saying the path out of the financial crisis and European debt problem is for individuals and governments around the world to cut back, Paul Krugman wants us to spend, spend, spend.

So how much we spend on supporting the economy in 2010 and 2011 is almost irrelevant to the fundamental budget picture. Why, then, are Very Serious People demanding immediate fiscal austerity?

The answer is, to reassure the markets — because the markets supposedly won’t believe in the willingness of governments to engage in long-run fiscal reform unless they inflict pointless pain right now. To repeat: the whole argument rests on the presumption that markets will turn on us unless we demonstrate a willingness to suffer, even though that suffering serves no purpose.

Krugman has of course been calling for additional stimulus spending for a while. So it may be easy to dismiss Krugman as a liberal who, despite his Nobel, is no longer in touch with economics. But he’s not the only one calling for more spending.

Besides Krugman, Martin Wolf of the Financial Times has been arguing against government cut backs in the wake of the economic slowdown as well.

This is all very well, many will respond, but what about the risks of a Greek-style meltdown? A year ago, I argued – in response to a vigorous public debate between the Harvard historian, Niall Ferguson, and the Nobel-laureate economist, Paul Krugman – that the rapid rise in US long-term interest rates was no more than a return to normal, after the panic. Subsequent developments strongly support this argument.

US government 10-year bond rates are a mere 3.2 per cent, down from 3.9 per cent on June 10 2009, Germany’s are 2.6 per cent, France’s 3 per cent and even the UK’s only 3.4 per cent. German rates are now where Japan’s were in early 1997, during the long slide from 7.9 per cent in 1990 to just above 1 per cent today. What about default risk? Markets seem to view that as close to zero. . . .

The question is whether such confidence will last. My guess – there is no certainty here – is that the US is more likely to be able to borrow for a long time, like Japan, than to be shut out of markets, like Greece, with the UK in-between.

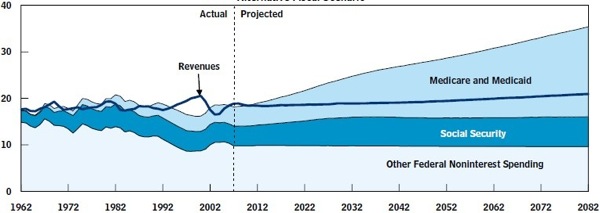

The debate here is between about what we should care about more: The current state of the economy or a perception about the long-term state of the economy. Because right now it seems in our best interest to spend more money on jobs programs, extending unemployment benefits and other stimulus programs. The problem is that all of that additional spending along with the current roughly $1.5 trillion deficit is going to get us into trouble. Krugman comes down on the side of it is more important to worry about people suffering now. The Tea Partiers, and many economists, care more about what the spending now could to the welfare of our children.

The problem with this argument, as Wolf points out, is that the bond market doesn’t see the Armageddon that the Tea Partiers, gold hoarders and other see. The 10-year bond yield is at historic lows. Now you can make the argument that markets are irrational. Technology stocks and houses were not as safe as we thought. And that may be true about US bonds as well. And so to send this country further into debt just because there is currently some bullishness in the bond market is foolish. Here’s Tyler Cowen making that very point:

In the blogosphere, discussions of market constraints are too heavily influenced by interest rates, which also “measure” an ongoing flight to safety. (U.S. rates have fallen of late, but does that mean our fiscal position has improved? Hardly.) . . . . The real interest is only one indicator of where fiscal policy is at. The point that interest rates serve multiple functions, and don’t always communicate direct market information very well, comes from…John Maynard Keynes. Let’s at least keep that possibility in mind.

Yes, the bond market should tell us everything. You have to believe it tells us something. National economies are very large. And they can turn around very quickly. It’s not like our own personal economics. Getting out of credit card debt is very tough. Our incomes down change very much, and our spending patterns are ingrained in who we are. The US economy does surprising things. Who knew that Clinton was going to be able to get us into a surplus situation. Who would have guess that Bush would have been able to screw that up so quickly. And what about the financial crisis. Economies are very hard to predict. Interest rates even more so. So policy makers should go with what they know. We don’t know what our current deficits will mean for our children or even interest rates a year from now. We do know that people are unemployed and suffering financially. I say go with that.

I subscribe, via rss, to Christopher Lydon’s

I subscribe, via rss, to Christopher Lydon’s