There’s been an argument floating around the econoblogs over the desirability of the Feds pushing down mortgage rates. Felix Salmon here makes the case against, and links to a couple of arguments on the other side.

Felix Salmon: Against Lower Mortgage Rates

Glenn Hubbard and Charlie Mayer have a WSJ op-ed saying, in the clear words of their headline, that "Low-Interest Mortgages Are the Answer"; Brad DeLong agrees, and yes, he’s more astonished than anybody else that he’s siding with Hubbard.

I, however, find the argument unconvincing.

First, Hubbard and Mayer imply that the house-price decline is now in overshooting territory: "while fundamental factors clearly played a role in driving down house prices that were at excessive levels two years ago," they write, "house values are today lower than what is consistent with the average level of affordability in the past 20 years".

This is an argument which basically says that nominal house prices don’t matter — all that matters is "affordability", which is code for low interest rates. In other words, they’re assuming their conclusion. Of course nominal interest rates matter: house-price declines, as we’ve seen, can cause massive delinquency and default. As a result, no one wants to live in a world where house prices would plunge if and when interest rates rise substantially.

Indeed, the authors’ own research, which shows relatively low levels of affordability 20 years ago when interest rates were high, only proves that nominal prices do matter. And as a glance at the Case-Shiller indices will show you, nominal house prices are still very high by historical standards.

There’s really no fundamental reason why Americans could and did become so comfortable with the concept of the million-dollar house, even while the average household income remained stubbornly in the five-digit range. And there’s no fundamental reason either why most families should essentially have to use one full-time salary just to pay the mortgage, and rely on a second full-time salary to actually spend and live on. If you’re looking at affordability in terms of household income, you’re missing the fact that many households have had to take on extra jobs just to afford their homes.

The op-ed continues:

A 4.5% mortgage rate is not too low. The 10-year U.S. Treasury yield closed at 2.3% on Dec. 12, 2008. Hence a 4.5% mortgage rate is 2.2% above the Treasury yield, above the 1.6% spread that would prevail in a normally functioning mortgage market.

But a 4.5% mortgage rate is too low, and as someone who sits on the board of a credit union which does a lot of real estate lending, I’m very aware of the fact.

Hubbard and Mayer, here, are careful again to ignore nominal levels: they look instead only at spreads over the bubblicious Treasury market. Yes, when Treasury yields are artificially low, then spreads over Treasuries are going to look wider than normal. But a 4.5% mortgage rate is unprecedented in modern times, if ever, and for good reason.

If banks could originate to distribute, like they did during the bubble, then they could happily lend out at 4.5% and not worry about the consequences of having an asset yielding 4.5% sitting on their books for 30 years. But as we’ve seen, the originate-to-distribute is a recipe for fraud and lax underwriting. Private-sector investors are now sensibly wary of it, and Frannie should be too.

On the other hand, if banks are really lending out 30-year funds at 4.5%, they’re taking an enormous amount of interest rate risk, which is not at all easy to hedge. Remember that the first round of Frannie scandals centered on the agencies’ inability to effectively hedge their interest-rate risk; there’s no reason to believe that private-sector mortgage lenders will be any better. When Fed funds goes back over 5% — which it’s bound to do at some point in the next 30 years –and banks have a whole bunch of 4.5% loans on their books, we’ll just have yet another banking crisis on our hands.

Hubbard and Mayer go on to calculate that lowering mortgate rates to 4.5% could lead to 2.4 million additional owner-occupied homes in 2009. That’s an enormous number, and it worries me greatly. We have too many owner-occupied homes already — one of the reasons we had a housing bubble in the first place was that a lot of people who had no business buying property went ahead and did so anyway.

In order for buying a home to be sensible, you basically need a predictably steady income and you need to expect to stay in the same place for the next 5-10 years. Are there 2.4 million non-homeowners who really fit that bill and who are remotely willing to buy a house in the next 12 months? Of course not. So if that many people do end up buying houses, a lot of them will end up either losing money — because they have to sell when they move and they’ll get hit with all the attendant fees and costs — or else missing out on opportunities which are too far from where they are stuck because they own a home somewhere. Or, of course, they’ll simply default.

The authors even go into a reverie about a $100-billion-a-year "housing wealth effect" — haven’t we learned anything from the bubble? The housing wealth effect is a by-product of home equity lines of credit and cash-out refinancings — the very instruments which caused the bubble and burdened Americans with far more debt than they could afford. There’s no housing wealth effect if you can’t borrow against your housing wealth — and, frankly, people shouldn’t be able to borrow against their housing wealth, certainly not as easily as they did over the past few years.

Hubbard and Mayer do have one good argument:

The 4.5% mortgage rate that the Treasury is considering also should be available for present homeowners who want to refinance, because of the benefits for the economy as a whole. We calculate that up to 34 million households would be able to do so, at an average monthly savings of $428 — or a total reduction in mortgage payments of $174 billion. This is a permanent reduction in payments and is thus likely to spur appreciable increases in consumption.

Moreover, trillions of dollars of refinancings would retire a large number of the existing mortgage-backed securities. This would reduce uncertainty about the value of existing mortgage-backed securities. It would flood the market with additional liquidity that the private sector could deploy to other uses such as auto loans, credit cards, commercial mortgages and general business lending.

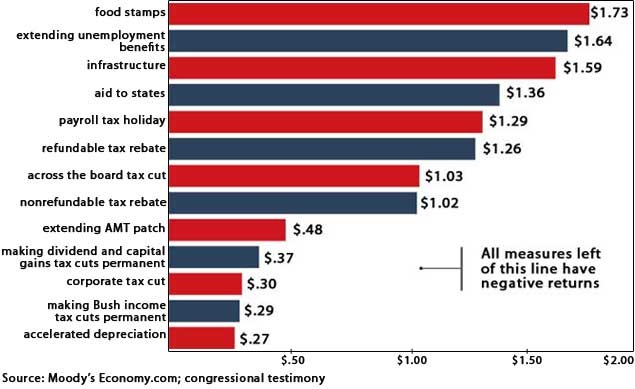

The multiplier here, however, is tiny: the cost to the government of reducing mortgage payments by $174 billion would be a good three times that sum.

There are much more effective ways for the government to spend half a trillion dollars than buying up mortgage-backed securities. Throwing it all at homeowners and leaving everybody else out in the cold is neither fair nor sensible.