John Stuart Mill was an early and strong advocate of universal suffrage, at a time when it was taken for granted that women, for example, did not vote. In Considerations on Representative Government, published in 1861, when the modern suffrage movement was just getting started, he wrote:

…it is a personal injustice to withhold from any one, unless for the prevention of greater evils, the ordinary privilege of having his voice reckoned in the disposal of affairs in which he has the same interest as other people. If he is compelled to pay, if he may be compelled to fight, if he is required implicitly to obey, he should be legally entitled to be told what for; to have his consent asked, and his opinion counted at its worth, though not at more than its worth. There ought to be no pariahs in a full-grown and civilised nation; no persons disqualified, except through their own default. Every one is degraded, whether aware of it or not, when other people, without consulting him, take upon themselves unlimited power to regulate his destiny. And even in a much more improved state than the human mind has ever yet reached, it is not in nature that they who are thus disposed of should meet with as fair play as those who have a voice. Rulers and ruling classes are under a necessity of considering the interests and wishes of those who have the suffrage; but of those who are excluded, it is in their option whether they will do so or not, and, however honestly disposed, they are in general too fully occupied with things which they must attend to, to have much room in their thoughts for anything which they can with impunity disregard. No arrangement of the suffrage, therefore, can be permanently satisfactory in which any person or class is peremptorily excluded; in which the electoral privilege is not open to all persons of full age who desire to obtain it.

Clear and unequivocal? Not quite as unequivocal as we, reading this with 21st-century eyes, might think. I don’t mean the “full age” qualification; we might argue over the age in question, but we generally accept an age qualification for voting. The catch shows up in the phrase “no persons disqualified, except through their own default” and again, “open to all persons of full age who desire to obtain it.”

Mill isn’t being coy. He explains in the very next paragraph how his vision of universal suffrage differs from our default idea of automatic universal suffrage.

There are, however, certain exclusions, required by positive reasons, which do not conflict with this principle, and which, though an evil in themselves, are only to be got rid of by the cessation of the state of things which requires them. I regard it as wholly inadmissible that any person should participate in the suffrage without being able to read, write, and, I will add, perform the common operations of arithmetic. Justice demands, even when the suffrage does not depend on it, that the means of attaining these elementary acquirements should be within the reach of every person, either gratuitously, or at an expense not exceeding what the poorest who earn their own living can afford. If this were really the case, people would no more think of giving the suffrage to a man who could not read, than of giving it to a child who could not speak; and it would not be society that would exclude him, but his own laziness. When society has not performed its duty, by rendering this amount of instruction accessible to all, there is some hardship in the case, but it is a hardship that ought to be borne. If society has neglected to discharge two solemn obligations, the more important and more fundamental of the two must be fulfilled first: universal teaching must precede universal enfranchisement. No one but those in whom an à priori theory has silenced common sense will maintain that power over others, over the whole community, should be imparted to people who have not acquired the commonest and most essential requisites for taking care of themselves; for pursuing intelligently their own interests, and those of the persons most nearly allied to them. This argument, doubtless, might be pressed further, and made to prove much more. It would be eminently desirable that other things besides reading, writing, and arithmetic could be made necessary to the suffrage; that some knowledge of the conformation of the earth, its natural and political divisions, the elements of general history, and of the history and institutions of their own country, could be required from all electors. But these kinds of knowledge, however indispensable to an intelligent use of the suffrage, are not, in this country, nor probably anywhere save in the Northern United States, accessible to the whole people; nor does there exist any trustworthy machinery for ascertaining whether they have been acquired or not. The attempt, at present, would lead to partiality, chicanery, and every kind of fraud. It is better that the suffrage should be conferred indiscriminately, or even withheld indiscriminately, than that it should be given to one and withheld from another at the discretion of a public officer. In regard, however, to reading, writing, and calculating, there need be no difficulty. It would be easy to require from every one who presented himself for registry that he should, in the presence of the registrar, copy a sentence from an English book, and perform a sum in the rule of three; and to secure, by fixed rules and complete publicity, the honest application of so very simple a test. This condition, therefore, should in all cases accompany universal suffrage; and it would, after a few years, exclude none but those who cared so little for the privilege, that their vote, if given, would not in general be an indication of any real political opinion.

We find (or at least I found, at first reading) this to be just a bit shocking, reading it through the lens of history, in particular Reconstruction and the Jim Crow South, aware as Mill was not of the pernicious use of literacy tests and poll taxes to prevent whole classes and races from voting, even after legal suffrage was granted.

On the other hand, it’s hard to see how a democracy can work if its citizens are throwing darts at their ballots or, worse, voting based on systematically bad information, something demagogues and soundbites make their living on.

To the extent that we try to address Mill’s concerns these days, it’s through voter education: media reporting, candidate debates and the like. But these can generate more heat than light, with he-said/she-said and horserace reporting, and “debates” that end up being extended exercises in message control.

This is, I believe, the central problem of the democratic project, and I’m completely at a loss for a solution.

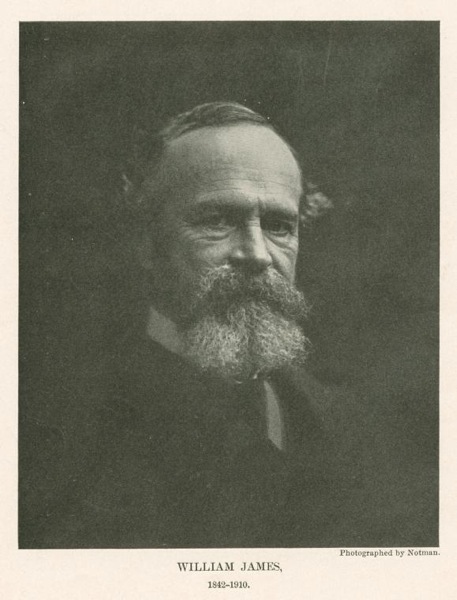

William James’ third son, Herman, died of whooping cough at the age of 18 months. Some 22 years later, James wrote in Pragmatism (he was 65):

William James’ third son, Herman, died of whooping cough at the age of 18 months. Some 22 years later, James wrote in Pragmatism (he was 65): I also wanted to mention a relatively recent (2006) biography, William James: In the Maelstrom of American Modernism. I picked up a hardcover copy from a bargain table in Minneapolis a year ago, and have been working my way through it ever since. It’s a reflection on my reading habits, not the quality of the writing, that a year later I’m only halfway through.

I also wanted to mention a relatively recent (2006) biography, William James: In the Maelstrom of American Modernism. I picked up a hardcover copy from a bargain table in Minneapolis a year ago, and have been working my way through it ever since. It’s a reflection on my reading habits, not the quality of the writing, that a year later I’m only halfway through.  Following up on my earlier

Following up on my earlier  Like most of my generation, I was brought up on the saying: ‘Satan finds some mischief for idle hands to do.’ Being a highly virtuous child, I believed all that I was told, and acquired a conscience which has kept me working hard down to the present moment. But although my conscience has controlled my actions, my opinions have undergone a revolution. I think that there is far too much work done in the world, that immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous, and that what needs to be preached in modern industrial countries is quite different from what always has been preached. Everyone knows the story of the traveler in Naples who saw twelve beggars lying in the sun (it was before the days of Mussolini), and offered a lira to the laziest of them. Eleven of them jumped up to claim it, so he gave it to the twelfth. this traveler was on the right lines. But in countries which do not enjoy Mediterranean sunshine idleness is more difficult, and a great public propaganda will be required to inaugurate it. I hope that, after reading the following pages, the leaders of the YMCA will start a campaign to induce good young men to do nothing. If so, I shall not have lived in vain. …

Like most of my generation, I was brought up on the saying: ‘Satan finds some mischief for idle hands to do.’ Being a highly virtuous child, I believed all that I was told, and acquired a conscience which has kept me working hard down to the present moment. But although my conscience has controlled my actions, my opinions have undergone a revolution. I think that there is far too much work done in the world, that immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous, and that what needs to be preached in modern industrial countries is quite different from what always has been preached. Everyone knows the story of the traveler in Naples who saw twelve beggars lying in the sun (it was before the days of Mussolini), and offered a lira to the laziest of them. Eleven of them jumped up to claim it, so he gave it to the twelfth. this traveler was on the right lines. But in countries which do not enjoy Mediterranean sunshine idleness is more difficult, and a great public propaganda will be required to inaugurate it. I hope that, after reading the following pages, the leaders of the YMCA will start a campaign to induce good young men to do nothing. If so, I shall not have lived in vain. …

Background: In a NY Times

Background: In a NY Times