The market can remain irrational for longer than you can remain solvent.

—John Maynard Keynes

A variation on Gambler’s Ruin.

via Sam Smith

jonathan lundell

Economics broadly construed: macro, micro, behavioral, money, finance.

The market can remain irrational for longer than you can remain solvent.

—John Maynard Keynes

A variation on Gambler’s Ruin.

via Sam Smith

Nouriel Roubini.

Mild signs that the rate of economic contraction is slowing in the United States, China and other parts of the world have led many economists to forecast that positive growth will return to the US in the second half of the year, and that a similar recovery will occur in other advanced economies.

The emerging consensus among economists is that growth next year will be close to the trend rate of 2.5 per cent.

Investors are talking of ‘green shoots’ of recovery and of positive ‘second derivatives of economic activity’ (continuing economic contraction is the first, negative, derivative, but the slower rate suggests that the bottom is near).

As a result, stock markets have started to rally in the US and around the world. Markets seem to believe that there is light at the end of the tunnel for the economy and for the battered profits of corporations and financial firms.

This consensus optimism is, I believe, not supported by the facts. …

via Brad DeLong

Yves Smith quotes generously from a Bloomberg interview with Joe Stiglitz. I’ll quote generously from her.

Stiglitz: Bank Plan Destined to Fail, Doomed By White House/Wall Street Ties

Big name economists continue their attacks on the Obama bank rescue programs. Yesterday Willem Buiter, one of Europe’s most highly respected macroeconomists, continued his salvos, contending that the funding was woefully inadequate to recapitalize or otherwise prop up financial firms. The longer the US delays winding up sick banks, the more time wasted and good money thrown after bad.

Nobel prize winner Joseph Sitglitz issued even blunter criticism today (and it’s hard to be more caustic than Buiter), accusing the Administration of wanting to aid industry incumbents rather than fix the system.

The worst is that the dim of criticism has been rising, yet Team Obama seems insistent on sticking with Plan A. At the rate they are going, they will succeed in proving the current system is beyond repair, and have spent enough firepower so as to have closed off other options.

The Obama administration’s plan to fix the U.S. banking system is destined to fail…“All the ingredients they have so far are weak, and there are several missing ingredients,” Stiglitz said in an interview. The people who designed the plans are “either in the pocket of the banks or they’re incompetent.”

The Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP, isn’t large enough to recapitalize the banking system, and the administration hasn’t been direct in addressing that shortfall, he said. Stiglitz said there are conflicts of interest at the White House because some of Obama’s advisers have close ties to Wall Street.

“We don’t have enough money, they don’t want to go back to Congress, and they don’t want to do it in an open way and they don’t want to get control” of the banks, a set of constraints that will guarantee failure, Stiglitz said.

The return to taxpayers from the TARP is as low as 25 cents on the dollar, he said. “The bank restructuring has been an absolute mess.”

Rather than continually buying small stakes in banks, weaker banks should be put through a receivership where the shareholders of the banks are wiped out and the bondholders become the shareholders, using taxpayer money to keep the institutions functioning, he said….

“You’re really bailing out the shareholders and the bondholders,” he said. “Some of the people likely to be involved in this, like Pimco, are big bondholders,” he said….

Stiglitz said taxpayer losses are likely to be much larger than bank profits from the PPIP program even though Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Chairman Sheila Bair has said the agency expects no losses.

“The statement from Sheila Bair that there’s no risk is absurd,” he said, because losses from the PPIP will be borne by the FDIC, which is funded by member banks.

“We’re going to be asking all the banks, including presumably some healthy banks, to pay for the losses of the bad banks,” Stiglitz said. “It’s a real redistribution and a tax on all American savers.”

Stiglitz was also concerned about the links between White House advisers and Wall Street. Hedge fund D.E. Shaw & Co. paid National Economic Council Director Lawrence Summers, a managing director of the firm, more than $5 million in salary and other compensation in the 16 months before he joined the administration. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner was president of the New York Federal Reserve Bank.

“America has had a revolving door. People go from Wall Street to Treasury and back to Wall Street,” he said. “Even if there is no quid pro quo, that is not the issue. The issue is the mindset.”…

He called the $787 billion stimulus program necessary but “flawed” because too much spending comes after 2009, and because it devotes too much of the money to tax cuts “which aren’t likely to work very effectively.”…

The $75 billion mortgage relief program, meanwhile, doesn’t do enough to help Americans who can’t afford to make their monthly payments, he said. It doesn’t reduce principal, doesn’t make changes in bankruptcy law that would help people work out debts, and doesn’t change the incentive to simply stop making payments once a mortgage is greater than the value of a house.

Stiglitz said the Fed, while it’s done almost all it can to bring the country back from the worst recession since 1982, can’t revive the economy on its own.

Relying on low interest rates to help put a floor under housing prices is a variation on the policies that created the housing bubble in the first place, Stiglitz said.

“This is a strategy trying to recreate that bubble,” he said. “That’s not likely to provide a long run solution. It’s a solution that says let’s kick the can down the road a little bit.”

While the strategy might put a floor under housing prices, it won’t do anything to speed the recovery, he said. “It’s a recipe for Japanese-style malaise.”

I give it six months before it becomes undeniable that the current system is hopelessly broken.

Paul Krugman.

… Dean Baker has argued for some time that, properly measured, the productivity gap between America and Europe never happened. I’m becoming more sympathetic to his point of view.

We all know that the upper tax brackets used to be a lot higher rates than they are now. But David Leonhardt points out that they didn’t kick in for most well-to-do incomes.

Richly Undeserved — Why Tax the Well Off as if They Were Wealthy?

It’s well known that tax rates on top incomes used to be far higher than they are today. The top marginal rate hovered around 90 percent in the 1940s, ’50s and early ’60s. Reagan ultimately reduced it to 28 percent, and it is now 35 percent. Obama would raise it to 39.6 percent, where it was under Bill Clinton.

What’s much less known is that those old confiscatory rates were not as sweeping as they sound. They applied to only the richest of the rich, because yesterday’s tax code, unlike today’s, had separate marginal tax rates for the truly wealthy and the merely affluent. For a married couple in 1960, for example, the 38 percent tax bracket started at $20,000, which is about $145,000 in today’s terms. The top bracket of 91 percent began at $400,000, which is the equivalent of nearly $3 million now. Some of the old brackets are truly stunning: in 1935, Franklin D. Roosevelt raised the top rate to 79 percent, from 63 percent, and raised the income level that qualified for that rate to $5 million (about $75 million today) from $1 million. As the economist Bruce Bartlett has noted, that 79 percent rate apparently applied to only one person in the entire country, John D. Rockefeller.

Today, by contrast, the very well off and the superwealthy are lumped together. The top bracket last year started at $357,700. Any income above that — whether it was the 400,000th dollar earned by a surgeon or the 40 millionth earned by a Wall Street titan — was taxed the same, at 35 percent. This change is especially striking, because there is so much more income at the top of the distribution now than there was in the past. Today a tax rate for the very top earners would apply to a far larger portion of the nation’s income than it would have years ago.

The worst isn’t over. Robert Reich edition.

… But we’re not at the beginning of the end. I’m not even sure we’re at the end of the beginning. All of these pieces of upbeat news are connected by one fact: the flood of money the Fed has been releasing into the economy. Of course mortage rates are declining, mortgage orginations are surging, and people and companies are borrowing more. So much money is sloshing around the economy that its price is bound to drop. And cheap money is bound to induce some borrowing. The real question is whether this means an economic turnaround. The answer is it doesn’t. …

Dean Baker.

There are several articles floating around with the general message that an uptick in the stock market or bank profits does not mean that the economy is finally “fixed”. I’ll try to post a couple Real Soon Now.

If Economists Knew Arithmetic, We Might Waste Less Money on Banks

There is no doubt that the economy would be better off if most of our banks were not insolvent, but only those who are really bad at arithmetic would think that repairing the banking system will restore prosperity. The economy would still be faced with a massive shortfall in demand with the unemployment rate soaring into the double digits.

The basic problem is that the economists who missed the housing bubble (EMHB) somehow still don’t understand how the bubble drove growth earlier in this decade. There were two main channels:

Residential construction expanded from its average of 4 percent of GDP to more than 6 percent of GDP at its peak in 2005; and

Consumption boomed based on ephemeral housing bubble wealth, as the adjusted saving rate turned negative over the years from 2004 to 2008, compared to a post World War II average of 8 percent.

The collapse of the bubble has derailed these engines of growth. Housing construction is now less than 3 percent of GDP and the adjusted saving rate is approaching its post-war average. This is why the economy is slumping and the unemployment rate is soaring. There is no sector that can readily fill a gap in demand in the neighborhood of 8-9 percentage points of GDP. …

There’s more, of course.

Yves Smith. Good stuff. Go read.

naked capitalism: Banks Whining Over TARP Repayment Terms

I have zero sympathy for the kvetching over the banks’ complaints over the supposedly onerous terms for repayment of TARP funds.

Simon Johnson, in a fascinating followup to his Atlantic piece, concludes:

… The big issue is of course the financial sector reform process. Some of my colleagues expressed great satisfaction with the progress made by the G20. But progressing down a blind alley is not something to be pleased about. I have yet to hear a single responsible official in any industrial country state what is obvious to most technocrats who are not currently officials: anything too big to fail is too big to exist.

If the bankers were just stupid, as suggested by David Brooks, then regulatory fixes might make some sense. But we know that bankers are smart, so it is their organizations that became stupid. What is the economic and political power structure that made it possible for such stupid organizations to become so large relative to the economy? Answer this and you address what we need to do going forward.

At a high profile conference in the run-up to this crisis, someone destined to become a leading official in the Obama Administration responded to a sensible technocratic critique of the financial system’s incentive structure (from the IMF, no less) by calling it “Luddite”. By all accounts, this is the prevailing attitude in today’s White House.

But the right metaphor is not breaking productive machines, or peasants with pitchforks, or even the poor vs. the rich. It’s as if the organizations running the nuclear power industry had shown themselves to be stupid and profoundly dangerous. You might wish to abolish nuclear power, but that is not a realistic option; storming power plants makes no sense; and the industry has captured all regulators ever sent after them.

The technocratic options are simple, (1) assume a better regulator, of a kind that has never existed on this face of this earth, (2) make banks smaller, less powerful, and much more boring.

Barry Ritholtz.

Geithner’s Stress Test “A Complete Sham”

The bank stress tests currently underway are “a complete sham,” says William Black, a former senior bank regulator and S&L prosecutor, and currently an Associate Professor of Economics and Law at the University of Missouri – Kansas City. “It’s a Potemkin model. Built to fool people.” Like many others, Black believes the “worst case scenario” used in the stress test don’t go far enough.

He detailed these and related concerns in a recent interview with Naked Capitalism. But Black, who was counsel to the Federal Home Loan Bank Board during the S&L Crisis, says the program’s failings go way beyond such technical issues. “There is no real purpose [of the stress test] other than to fool us. To make us chumps,” Black says. Noting policymakers have long stated the problem is a lack of confidence, Black says Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner is now essentially saying: “’If we lie and they believe us, all will be well.’ It’s Orwellian.”

John Cole passes along this concise WSJ account of the events leading to the present crash.

The 2001 recession might have ended the bubble, but the Federal Reserve decided to pursue an unusually expansionary monetary policy in order to counteract the downturn. When the Fed increased liquidity, money naturally flowed to the fastest expanding sector. Both the Clinton and Bush administrations aggressively pursued the goal of expanding homeownership, so credit standards eroded. Lenders and the investment banks that securitized mortgages used rising home prices to justify loans to buyers with limited assets and income. Rating agencies accepted the hypothesis of ever rising home values, gave large portions of each security issue an investment-grade rating, and investors gobbled them up.

…and everybody lived happily ever after.

Joseph Stiglitz chimes in.

… What the Obama administration is doing is far worse than nationalization: it is ersatz capitalism, the privatizing of gains and the socializing of losses. It is a “partnership” in which one partner robs the other. And such partnerships — with the private sector in control — have perverse incentives, worse even than the ones that got us into the mess.

So what is the appeal of a proposal like this? Perhaps it’s the kind of Rube Goldberg device that Wall Street loves — clever, complex and nontransparent, allowing huge transfers of wealth to the financial markets. It has allowed the administration to avoid going back to Congress to ask for the money needed to fix our banks, and it provided a way to avoid nationalization.

But we are already suffering from a crisis of confidence. When the high costs of the administration’s plan become apparent, confidence will be eroded further. At that point the task of recreating a vibrant financial sector, and resuscitating the economy, will be even harder.

John Quiggin, restating the obvious.

Rawls, Cohen and the Laffer hypothesis

… There’s very little reason to believe the Laffer hypothesis or equivalent claims about the banks. The reason tax rates aren’t higher and bankers are getting bailed out on hugely generous terms isn’t because Rawlsians have outvoted Cohenites behind the veil of ignorance, or even because lots of economists believe the Laffer hypothesis. It’s because the rich and powerful are, well, rich and powerful. Not only can they promote ideas, however dubious, that serve their cause, they can bring powerful force to bear against any government or political movement that threatens their interest. All of this is obvious enough, but after thirty years in which any mention of these facts has been shouted down as the “politics of envy” or “class hatred”, it may be necessary to restate the obvious. …

Here’s a meta-quandry: I categorized this post (and a couple of other recent posts) under Politics as well as Economics. I’ve been debating the wisdom of doing so, though. In the past, I’ve tended to omit the Politics category on the grounds of redundancy, at least within the context of this blog. What to do…

Edward Harrison at Naked Capitalism.

Barack Obama as Herbert Hoover

Edward Harrison here. For months now, we have been hearing the Obama — FDR comparisons, all suggesting that Barack Obama is a modern day Franklin Delano Roosevelt, with the opportunity to lead us out of Depression with a new New Deal. I have some serious problems with this comparison. In my view, a comparison between Barack Obama and Herbert Hoover is more apt. …

… This recession turned into the Great Depression, with the economy hitting bottom in March 1933. So, the entire recession we remember as being the depths of the Great Depression occurred while Herbert Hoover was President, not during FDR’s presidency. …

Why does this matter? Go read the post.

Your Tax Dollars at Work: Bailing Out Goldman Execs on Bad Bets

Hey, we’re all in this together. So, when an a worker loses their job, we give them a couple hundred of dollars a week for unemployment benefits. Or, if a mother working at a minimum wage job can’t buy health care for their kids, the government helps pick up the tab. Or, if some of the top executives at Goldman Sachs lose a fortune on their investments, Goldman uses taxpayer dollars to get them through the tough times, lending or giving them millions of dollars. Good reporting by the NYT.

—Dean Baker

The executives in question were “short on cash”. Not any more, it appears.

The other longish piece I’ve been meaning to recommend is this one by Jamie Galbraith.

… The oddest thing about the Geithner program is its failure to act as though the financial crisis is a true crisis—an integrated, long-term economic threat—rather than merely a couple of related but temporary problems, one in banking and the other in jobs. In banking, the dominant metaphor is of plumbing: there is a blockage to be cleared. Take a plunger to the toxic assets, it is said, and credit conditions will return to normal. This, then, will make the recession essentially normal, validating the stimulus package. Solve these two problems, and the crisis will end. That’s the thinking.

But the plumbing metaphor is misleading. Credit is not a flow. It is not something that can be forced downstream by clearing a pipe. Credit is a contract. It requires a borrower as well as a lender, a customer as well as a bank. And the borrower must meet two conditions. One is creditworthiness, meaning a secure income and, usually, a house with equity in it. Asset prices therefore matter. With a chronic oversupply of houses, prices fall, collateral disappears, and even if borrowers are willing they can’t qualify for loans. The other requirement is a willingness to borrow, motivated by what Keynes called the “animal spirits” of entrepreneurial enthusiasm. In a slump, such optimism is scarce. Even if people have collateral, they want the security of cash. And it is precisely because they want cash that they will not deplete their reserves by plunking down a payment on a new car.

The credit flow metaphor implies that people came flocking to the new-car showrooms last November and were turned away because there were no loans to be had. This is not true—what happened was that people stopped coming in. And they stopped coming in because, suddenly, they felt poor.

Strapped and afraid, people want to be in cash. This is what economists call the liquidity trap. And it gets worse: in these conditions, the normal estimates for multipliers—the bang for the buck—may be too high. Government spending on goods and services always increases total spending directly; a dollar of public spending is a dollar of GDP. But if the workers simply save their extra income, or use it to pay debt, that’s the end of the line: there is no further effect. For tax cuts (especially for the middle class and up), the new funds are mostly saved or used to pay down debt. Debt reduction may help lay a foundation for better times later on, but it doesn’t help now. With smaller multipliers, the public spending package would need to be even larger, in order to fill in all the holes in total demand. Thus financial crisis makes the real crisis worse, and the failure of the bank plan practically assures that the stimulus also will be too small. …

Galbraith does have recommendations—four of them. Here’s one:

Second, we should offset the violent drop in the wealth of the elderly population as a whole. The squeeze on the elderly has been little noted so far, but it hits in three separate ways: through the fall in the stock market; through the collapse of home values; and through the drop in interest rates, which reduces interest income on accumulated cash. For an increasing number of the elderly, Social Security and Medicare wealth are all they have.

That means that the entitlement reformers have it backward: instead of cutting Social Security benefits, we should increase them, especially for those at the bottom of the benefit scale. Indeed, in this crisis, precisely because it is universal and efficient, Social Security is an economic recovery ace in the hole. Increasing benefits is a simple, direct, progressive, and highly efficient way to prevent poverty and sustain purchasing power for this vulnerable population. I would also argue for lowering the age of eligibility for Medicare to (say) fifty-five, to permit workers to retire earlier and to free firms from the burden of managing health plans for older workers.

This suggestion is meant, in part, to call attention to the madness of talk about Social Security and Medicare cuts. The prospect of future cuts in this modest but vital source of retirement security can only prompt worried prime-age workers to spend less and save more today. And that will make the present economic crisis deeper. In reality, there is no Social Security “financing problem” at all. There is a health care problem, but that can be dealt with only by deciding what health services to provide, and how to pay for them, for the whole population. It cannot be dealt with, responsibly or ethically, by cutting care for the old.

How likely is that? Well, it’s probably the likeliest of his four suggestions. Not very, I’d say.

Simon Johnson has a terrific article at The Atlantic Online. It’s long and worth reading. I’m still working my way through it, but I thought I’d post a couple of short bits along with the link.

… But I must tell you, to IMF officials, all of these crises looked depressingly similar. Each country, of course, needed a loan, but more than that, each needed to make big changes so that the loan could really work. Almost always, countries in crisis need to learn to live within their means after a period of excess—exports must be increased, and imports cut—and the goal is to do this without the most horrible of recessions. Naturally, the fund’s economists spend time figuring out the policies—budget, money supply, and the like—that make sense in this context. Yet the economic solution is seldom very hard to work out.

No, the real concern of the fund’s senior staff, and the biggest obstacle to recovery, is almost invariably the politics of countries in crisis.

Typically, these countries are in a desperate economic situation for one simple reason—the powerful elites within them overreached in good times and took too many risks. Emerging-market governments and their private-sector allies commonly form a tight-knit—and, most of the time, genteel—oligarchy, running the country rather like a profit-seeking company in which they are the controlling shareholders. When a country like Indonesia or South Korea or Russia grows, so do the ambitions of its captains of industry. As masters of their mini-universe, these people make some investments that clearly benefit the broader economy, but they also start making bigger and riskier bets. They reckon—correctly, in most cases—that their political connections will allow them to push onto the government any substantial problems that arise.

In Russia, for instance, the private sector is now in serious trouble because, over the past five years or so, it borrowed at least $490 billion from global banks and investors on the assumption that the country’s energy sector could support a permanent increase in consumption throughout the economy. As Russia’s oligarchs spent this capital, acquiring other companies and embarking on ambitious investment plans that generated jobs, their importance to the political elite increased. Growing political support meant better access to lucrative contracts, tax breaks, and subsidies. And foreign investors could not have been more pleased; all other things being equal, they prefer to lend money to people who have the implicit backing of their national governments, even if that backing gives off the faint whiff of corruption.

But inevitably, emerging-market oligarchs get carried away; they waste money and build massive business empires on a mountain of debt. Local banks, sometimes pressured by the government, become too willing to extend credit to the elite and to those who depend on them. Overborrowing always ends badly, whether for an individual, a company, or a country. Sooner or later, credit conditions become tighter and no one will lend you money on anything close to affordable terms.

The downward spiral that follows is remarkably steep. Enormous companies teeter on the brink of default, and the local banks that have lent to them collapse. Yesterday’s “public-private partnerships” are relabeled “crony capitalism.” With credit unavailable, economic paralysis ensues, and conditions just get worse and worse. The government is forced to draw down its foreign-currency reserves to pay for imports, service debt, and cover private losses. But these reserves will eventually run out. If the country cannot right itself before that happens, it will default on its sovereign debt and become an economic pariah. The government, in its race to stop the bleeding, will typically need to wipe out some of the national champions—now hemorrhaging cash—and usually restructure a banking system that’s gone badly out of balance. It will, in other words, need to squeeze at least some of its oligarchs.

Squeezing the oligarchs, though, is seldom the strategy of choice among emerging-market governments. Quite the contrary: at the outset of the crisis, the oligarchs are usually among the first to get extra help from the government, such as preferential access to foreign currency, or maybe a nice tax break, or—here’s a classic Kremlin bailout technique—the assumption of private debt obligations by the government. Under duress, generosity toward old friends takes many innovative forms. Meanwhile, needing to squeeze someone, most emerging-market governments look first to ordinary working folk—at least until the riots grow too large.

Eventually, as the oligarchs in Putin’s Russia now realize, some within the elite have to lose out before recovery can begin. It’s a game of musical chairs: there just aren’t enough currency reserves to take care of everyone, and the government cannot afford to take over private-sector debt completely.

So the IMF staff looks into the eyes of the minister of finance and decides whether the government is serious yet. The fund will give even a country like Russia a loan eventually, but first it wants to make sure Prime Minister Putin is ready, willing, and able to be tough on some of his friends. If he is not ready to throw former pals to the wolves, the fund can wait. And when he is ready, the fund is happy to make helpful suggestions—particularly with regard to wresting control of the banking system from the hands of the most incompetent and avaricious “entrepreneurs.”

Of course, Putin’s ex-friends will fight back. They’ll mobilize allies, work the system, and put pressure on other parts of the government to get additional subsidies. In extreme cases, they’ll even try subversion—including calling up their contacts in the American foreign-policy establishment, as the Ukrainians did with some success in the late 1990s. …

Well, you can see where this is going. Pay attention, now.

… But these various policies—lightweight regulation, cheap money, the unwritten Chinese-American economic alliance, the promotion of homeownership—had something in common. Even though some are traditionally associated with Democrats and some with Republicans, they all benefited the financial sector. Policy changes that might have forestalled the crisis but would have limited the financial sector’s profits—such as Brooksley Born’s now-famous attempts to regulate credit-default swaps at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, in 1998—were ignored or swept aside. …

Johnson is not exactly optimistic.

… The conventional wisdom among the elite is still that the current slump “cannot be as bad as the Great Depression.” This view is wrong. What we face now could, in fact, be worse than the Great Depression—because the world is now so much more interconnected and because the banking sector is now so big. We face a synchronized downturn in almost all countries, a weakening of confidence among individuals and firms, and major problems for government finances. If our leadership wakes up to the potential consequences, we may yet see dramatic action on the banking system and a breaking of the old elite. Let us hope it is not then too late.

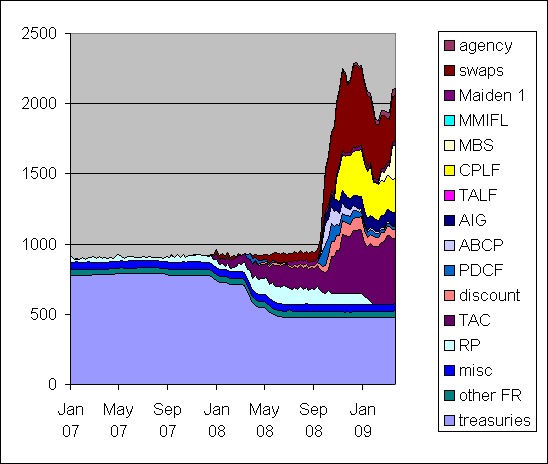

Johnson is no wild-eyed prophet of doom. While the Fed and the US Treasury are being operated by Johnson’s elites, or at least their BFFs, we can see that those folks are no less concerned. Here’s a graph of Fed lending for the last couple of years, from a longer posting by Mark Thoma (also worth reading):

That’s trillions of dollars being pushed into reserves. This is not business as usual.

A note on budget deficits from Dean Baker. FIrst put out the fire; then mow the lawn.

Budget Deficits and Blow Up Dolls: It’s the Economy Stupid!

In the movie Lars and the Real Girl, the main character imagines that a female blow-up doll is his fiancée. To humor Lars, his brother and sister-in-law go along with the charade. Over the course of the movie, more people are drawn into the circle, until eventually the whole town is treating Bianca the blow-up doll as one of its leading citizens. …

People are losing their homes through foreclosures at the rate of more than 100,000 a month. The default rates on credit cards, car loans and other debt is at record levels. Most of our major banks are effectively insolvent.

Home and stock prices have plummeted, destroying most of the wealth of the baby boom cohort as they stand on the edge of retirement. The economy is shedding almost 700,000 jobs a month, with the unemployment rate rapidly approaching the highest level since the Great Depression.

In this context we are supposed to be up in arms over the deficit projections for 2013 or 2019? This is a bit like someone complaining about the lawn not being mowed at a time when the house is on fire, it’s just not the first priority. And the media all seem to go along with the charade — yes, they are very concerned about the projected deficit for 2013, just as the characters in the movie expressed concern about the health of Bianca the blow-up doll. …

OK, a bitter joke, but that’s the way we like ’em these days.

Why Is “Buy America” Okay for Banks, but Not Steel?

Those damn protectionists in the Obama administration obviously don’t know anything about economics. How else can we explain the decision to require that the fund managers in their bank bailout plan must be headquartered in the United States.

I can’t wait to see the outraged and condescending editorials in the Washington Post and elsewhere explaining how protectionism is not the way to promote jobs and growth.

(Credit for the protectionism detection goes to my former colleague Heather Boushey, who can now be found at the Center for American Progress.)

—-Dean Baker

The AIG bonus flap is an unwelcome distraction from the main event, for more than one reason, not least because, if the “bonuses” are clawed back, somebody might be deluded into thinking that something has actually been accomplished.

First Hilzoy:

Even though I am furious at the people who brought down AIG, along with all the other Masters of the Universe, I do not support the House bill that passed yesterday — the one that would tax bonuses at 90%. For starters, it’s badly targeted. On the one hand, it leaves out the incredibly troubling Merrill Lynch bonuses, along with any other bonuses paid before Jan. 1 of this year. On the other hand, it hits people who were just writing life insurance policies at AIG. Moreover, it also hits anyone AIG hires now. Suppose, for instance, that AIG were to hire Paul Krugman to supervise the liquidation of its Financial Products Division. And suppose AIG wanted to pay him a bonus if he did his job quickly and well. His bonus would be taxed under this bill, even though he had nothing to do with the financial crisis (which is why I picked him), and is being given a bonus for helping to solve it.

The bill would also allow firms receiving TARP funds to avoid the tax by simply paying their employees exorbitant salaries. Bonuses are bad, but exactly the same amount of money paid to exactly the same employee in the form of a salary is apparently fine. This seems exactly backwards to me. Part of the problem with the AIG bonuses was precisely that they were not tied to performance in any way: the people at AIG-FP, who had gotten enormous amounts of money when times were good, supposedly on the basis of their performance, locked down the same level of compensation when it looked as though their trades were about to go bad. Now, apparently, we want to give people an enormous incentive to decouple their compensation from performance in exactly the same way. Oh goody.…

Then Robert Reich:

… Angry populism thrives on stories about the rich and privileged who use their influence to get cushy deals for themselves at the expense of the rest of us. AIG’s bonuses provide a perfect example. It’s too bad the same populist outrage doesn’t extend to issues involving far more money, affecting many more people, and entailing far more insidious abuses of power. Congress’s potemkin populism over AIG’s bonuses disguises business as usual when it comes to the really big stuff.