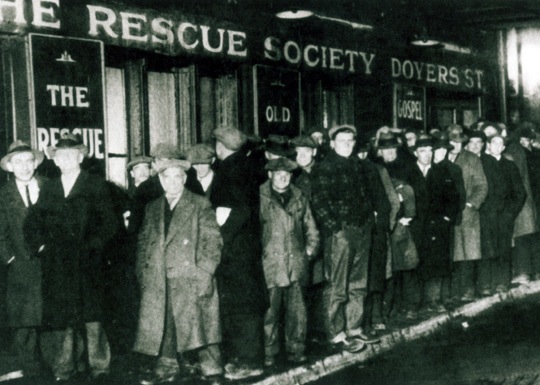

Rob Kapilow talks about the Harburg/Gorney 1932 classic on NPR. It sounds alarmingly up to date, adjusted for inflation.

The article has links to several renditions of the song, of which Harburg’s is my favorite (though Daniel Schorr’s version, at the end of the audio version, is quite fine). YouTube has a perfectly awful version by George Michael, and a rather interesting performance by Mandy Patinkin on the David Letterman set. The audience isn’t sure whether it’s not an extended joke, but Patinkin sells it pretty well.

Susan Stamberg has a blog post on the piece, where Roger Hurwitz adds in comments:

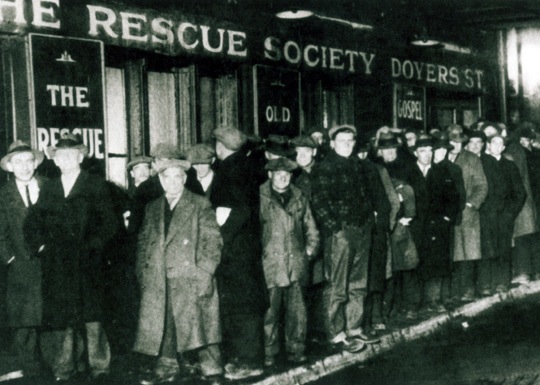

The interview, which Susan references, was with the late Studs Terkel and appears in his recently published P.S. (New Press, 2008). In it Harburg said about the song “it was trying to expound a social theory… that our whole system of capitalism and free enterprise is based a rather illogical and unscientific groundwork: that we each exploit each other, we each get as much out of the wealth of the world that our ruthlessness… gives us permission to enjoy. and most people who don’t have that kind of power are left penniless, even though they do most of the producing.”

Harburg went on to say that if Cole Porter had written the song, the singer would be the man asked for the dime and would have given a half-dollar.

Patricia Spaeth, commenting on the main article, rightly complains that Kapilow ignores the verse; let’s have the whole thing, shall we?

Brother, Can You Spare a Dime

lyrics by Yip Harburg, music by Jay Gorney (1931)

They used to tell me I was building a dream, and so I followed the mob,

When there was earth to plow, or guns to bear, I was always there right on the job.

They used to tell me I was building a dream, with peace and glory ahead,

Why should I be standing in line, just waiting for bread?

Once I built a railroad, I made it run, made it race against time.

Once I built a railroad; now it’s done. Brother, can you spare a dime?

Once I built a tower, up to the sun, brick, and rivet, and lime;

Once I built a tower, now it’s done. Brother, can you spare a dime?

Once in khaki suits, gee we looked swell,

Full of that Yankee Doodly Dum,

Half a million boots went slogging through Hell,

And I was the kid with the drum!

Say, don’t you remember, they called me Al; it was Al all the time.

Why don’t you remember, I’m your pal? Buddy, can you spare a dime?

Once in khaki suits, gee we looked swell,

Full of that Yankee Doodly Dum,

Half a million boots went slogging through Hell,

And I was the kid with the drum!

Say, don’t you remember, they called me Al; it was Al all the time.

Say, don’t you remember, I’m your pal? Buddy, can you spare a dime?