A Partisan Post, You Have Been Warned

Last night I read a post by Brad DeLong that made me so mad I had trouble falling asleep. (Not at DeLong, mind you.) There’s really nothing unusual in there — hysteria about the deficit, people who voted for the Bush tax cuts and the unfunded Medicare prescription drug benefit but suddenly think the national debt is killing us, political pandering — but maybe it was the proverbial straw.

First, let me say that I largely agree with DeLong here:

“I am–in normal times–a deficit hawk. I think the right target for the deficit in normal times is zero, with the added provision that when there are foreseeable future increases in spending shares of GDP we should run a surplus to pay for those foreseeable increases in an actuarially-sound manner. I think this because I know that there will come abnormal times when spending increases are appropriate. And I think that the combination of (a) actuarially-sound provision for future increases in spending shares and (b) nominal balance for the operating budget in normal times will create the headroom for (c) deficit spending in emergencies when it is advisable while (d) maintaining a non-explosive path for the debt as a whole.”

Now, let me tell you what I am sick of:

1. People who insist that the recent change in our fiscal spending is the product of high spending, without looking at the numbers, because their political priors are so strong they assume that high deficits under a Democratic president must be due to runaway spending. And it’s not just Robert Samuelson.

2. People who forecast the end of the world without pointing out why the world is ending. Here’s Niall Ferguson, in an article entitled “An Empire at Risk:”

“The deficit for the fiscal year 2009 came in at more than $1.4 trillion—about 11.2 percent of GDP, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). That’s a bigger deficit than any seen in the past 60 years—only slightly larger in relative terms than the deficit in 1942.”

But does he mention that the reason for the 2009 deficit is lower tax revenues due to the financial crisis and recession? No.

Here’s Ferguson on the 10-year projection:

“Meanwhile, in dollar terms, the total debt held by the public (excluding government agencies, but including foreigners) rises from $5.8 trillion in 2008 to $14.3 trillion in 2019—from 41 percent of GDP to 68 percent.”

Does he mention that, as early as January 2008, that number was projected to fall to 22%, and the majority of the change is due to lower tax revenues? No.

3. People who posture about our fiscal crisis who voted for the Bush tax cuts — shouldn’t shame require them to keep silent?

4. People who say, like Judd Gregg, “after the possibility of a terrorist getting a weapon of mass destruction and using it against us somewhere here in the United States, the single biggest threat that we face as a nation is the fact that we’re on a course toward fiscal insolvency,” as if this is a new problem, when it’s been around since 2004 (see Figure 1) — when, I might add, Judd Gregg was a member of the majority.

(Tell me, was Niall Ferguson forecasting the end of the American empire in 2004, when everything he says now about long-term entitlement spending was already true? That’s a real question.)

5. People who say that we can’t pass health care reform because it costs too much, ignoring the fact that the CBO projects the bills to be roughly deficit neutral, ignoring the fact that the Senate bill has received bipartisan health-economist support for its cost-cutting measures, and ignoring the fact that our long-term fiscal problem is, and always has been, about health care costs (see Figure 2).

6. People who say the Obama administration is weak on the deficit (Ferguson refers to Obama’s “indecision on the deficit”, and he is gentle by Republican standards), when by tackling health care costs head-on — and in the process angering their political base — they are doing the absolute most important thing necessary to solve the long-term debt problem.

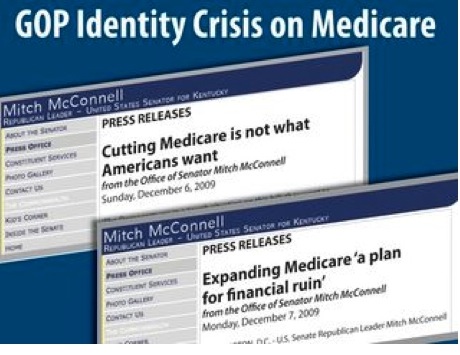

7. People who cite “financial ruin” purely, absolutely, incontrovertibly as a political tactic to try to kill health care reform (courtesy of DeLong and Brian Beutler):

8. Joe Lieberman.

By James Kwak

The Monks of Cool, whose tiny and exclusive moiynterass hidden in a really cool and laid-back valley in the lower Ramtops, have a passing-out test for a novice. He is taken into a room full of all types of clothing and asked: Yob9, my son, which of these is the most stylish thing to wear? And the correct answer is: Hey, whatever I select.b9 Cool, but not necessarily up to date. Terry Pratchett, Lords and Ladies , 1992 I’m not an economist and I probably don’t understand a lot about the EMH but I’ve always thought that the above quote is very similar to the price-is-right part. To put it in another way, I think it’s wrong to say that the price is right since we don’t really have anything to measure it against. If we did we’d already know the right price and we wouldn’t need the market. The way I see it, the right way to put it is that we don’t have any mechanism to set the price because it’s dependent on transient conditions of supply and demand and a large number of bits of information that we can’t objectively evaluate (or even be aware of). Therefore we can’t really tell what the right price is. So the right price is whatever the market, much like the novice monk, selects since it presumably incorporates all the relevant information. That’s not really wrong but if you put it that way it’s clearly tautological. And as such it’s not really useful (what good is it to know that A=A?). The question about bubbles brings the tautology, and eventually the usefulness of EMH to focus: if the market price is always right by definition there’s no such thing as a bubble (some people argue that this is true, read for example Krugman’s blog post Ketchup and the housing bubble ). Since it is obvious to most people that there are in fact bubbles, EMH proponents usually explain away the phenomenon by attributing the price anomalies to external factors (i.e. the government). This is dodgy: it is not clear why government intervention differs from other information already successfuly incorporated into the market determined price (and which is by definition right ). It sounds a lot like an ad hoc explanation for something that would disprove the hypothesis. If the price seems ok the market has clearly worked it’s magic, if it doesn’t then someone else is to blame. Which brings us to another point: since it’s shaped like a tautology and supported by ad hoc explanations it seems EMH is not falsifiable and therefore highly questionable.Sorry for the wall of text, it’s just the thoughts of a layman.CheersKyriakos (from far away, I’m European great blog btw, congrats)