I’ve been linking to and quoting Dean Baker on the bailout, generally because I’m inclined to agree with his take on the whole thing. But what do I know?

It concerns me that several economists whose views I respect take, mostly with some reluctance, a contrary view.

James Galbraith, for example:

In short, as I said at the beginning, the bill is a vast improvement over the original Treasury proposal. Given the choice between approving or defeating the bill as it stands, I would urge supporting the bill. I do so without illusions. There need be no pretense that it will solve our underlying financial and economic problems. It will not. The purpose, in my view, is to get the financial system and the economy through the year, and into the hands of the next administration. That is a limited purpose, but a legitimate purpose. And it may be the most that can be accomplished for the time being.

Nathan Newman:

Now, the final negotiated bill could have been a lot better. There should be tougher oversight, a better guaranteed equity share for taxpayers, a better deal for homeowners facing foreclosure, and, in the longer term, a commitment to using this new consolidation of home mortgages in the hands of the government to promote affordable housing more broadly. And if we want to go after the wealthy, we can do that explicitly through the tax code by raising taxes on dividends, capital gains and the wage income of high-income individuals. If there are any losses to taxpayers, it would be good to build in increased taxes or a financial transaction tax to automatically kick in to pay off those debts.

But we need some bill to create an alternative to these crazy Fed bailouts that are just helping Citibank, JP Morganchase and Bank of America become financial megabanks that will just dominate the economic landscape soon. I’d rather move assets into taxpayer hands that further strengthen a handful of these megabanks.

Joseph Stiglitz (also here):

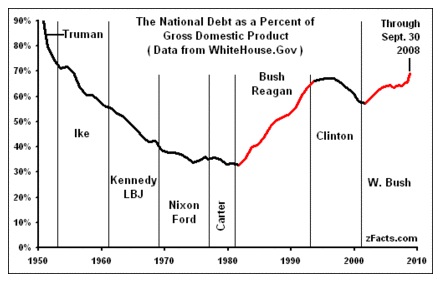

Perhaps by the time this article is published, the administration and Congress will have reached an agreement. No politician wants to be accused of being responsible for the next Great Depression by blocking key legislation. By all accounts, the compromise will be far better than the bill originally proposed by Paulson but still far short of what I have outlined should be done. No one expects them to address the underlying causes of the problem: the spirit of excessive deregulation that the Bush Administration so promoted. Almost surely, there will be plenty of work to be done by the next president and the next Congress. It would be better if we got it right the first time, but that is expecting too much of this president and his administration.

And Paul Krugman, all over the case. Stiglitz argues that something needs to be done, though it’s not entirely clear if he’s in the “better than nothing” camp with respect to the present bill.

All in all, there’s a distinct sense of a stampede.

Let’s close with a bit more of Dean Baker, who seems resigned to passage.

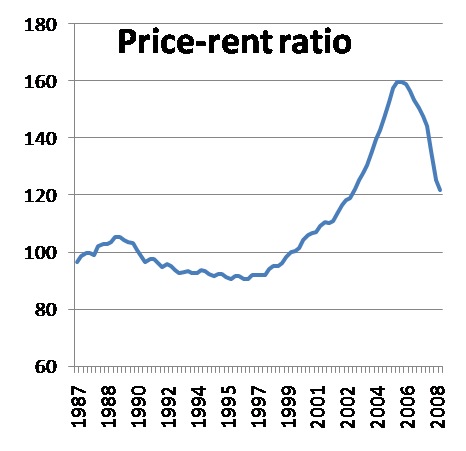

As a very large number of economists have argued, this bailout is fundamentally flawed in its design. It should be focused on directly injecting capital into the banking system, not overpaying for bad assets. This design flaw makes the bailout far less effective. Furthermore, this bill does almost nothing to offset the contractionary effect from the collapse of an $8 trillion housing bubble. For these reasons, it is not just morally repugnant to give taxpayer dollars to incompetent Wall Street bankers, it is also bad economic policy.

So here’s the deal. One simple measure of the success of the bailout is whether it fixes the mess. Will it be sufficient to restore the banking system or will we need still more money six months or a year down the road? Suppose it does?

Will our political leaders, who promised us that this bailout is the essential medicine for the economy, just get up and tell us that they need still more money? If our political leaders believe what they are telling the public, then they should be prepared to take responsibility for the success or failure of their policy. Are there any commitments to resign leadership positions in the event this great policy fails?

Update: I meant to add that I take the no votes of Russ Feingold and Bernie Sanders as strong political (vs primarily economic) reinforcement of the no position. Here’s Sanders:

If we are going to bail out Wall Street, it should be those people who have caused the problem, those people who have benefited from Bush’s tax breaks for millionaires and billionaires, those people who have taken advantage of deregulation, those people are the people who should pick up the tab, and not ordinary working people. I introduced an amendment which gave the Senate a very clear choice. We can pay for this bailout of Wall Street by asking people all across this country, small businesses on Main Street, homeowners on Maple Street, elderly couples on Oak Street, college students on Campus Avenue, working families on Sunrise Lane, we can ask them to pay for this bailout. That is one way we can go. Or, we can ask the people who have gained the most from the spasm of greed, the people whose incomes have been soaring under president bush, to pick up the tab.

“I proposed to raise the tax rate on any individual earning $500,000 a year or more or any family earning $1 million a year or more by 10 percent. That increase in the tax rate, from 35 percent to 45 percent, would raise more than $300 billion in the next five years, almost half the cost of the bailout. If what all the supporters of this legislation say is correct, that the government will get back some of its money when the market calms down and the government sells some of the assets it has purchased, then $300 billion should be sufficient to make sure that 99.7 percent of taxpayers do not have to pay one nickel for this bailout.

Most of my constituents did not earn a $38 million bonus in 2005 or make over $100 million in total compensation in three years, as did Henry Paulson, the current secretary of the Treasury, and former CEO of Goldman Sachs. Most of my constituents did not make $354 million in total compensation over the past five years as did Richard Fuld of Lehman Brothers. Most of my constituents did not cash out $60 million in stock after a $29 billion bailout for Bear Stearns after that failing company was bought out by J.P. Morgan Chase. Most of my constituents did not get a $161 million severance package as E. Stanley O’Neill, former CEO Merrill Lynch did.

Last week I placed on my Web site, www.sanders.senate.gov, a letter to Secretary Paulson in support of my amendment. It said that it should be those people best able to pay for this bailout, those people who have made out like bandits in recent years, they should be asked to pay for this bailout. It should not be the middle class. To my amazement, some 48,000 people cosigned this petition, and the names keep coming in. The message is very simple: “We had nothing to do with causing this bailout. We are already under economic duress. Go to those people who have made out like bandits. Go to those people who have caused this crisis and ask them to pay for the bailout.”

* “me” being

* “me” being