I first came across Andrew Brown through his fine 1999 book The Darwin Wars (jacket blurb from Daniel Dennett: ‘I wouldn’t admit it if Andrew Brown were my friend. What a sleazy bit of trash journalism’).

Much of Brown’s beat has been coverage of religion (in the UK), and he approaches the subject with considerable sympathy. The “wars” in the Darwin book are not centrally religious (well, not in the God sense), since the subject is primarily internecine intellectual battles, not evolution vs creationism. But buried in a footnote was a signal to me that Brown and I shared a particular point of view: “The clearest and most delightful example of how to think about religious belief is still William James’s The Varieties of Religion Experience” (p171 in the 1999 UK edition). Indeed.

Like Brown, I came to recognize the virtues of Varieties rather late. My undergraduate focus was on the later Wittgenstein, and while of course I encountered James, he didn’t really click with me until I reread Varieties (and subsequently a great deal more of James) decades later.

[A digression: there seems to me to be an affinity between the later James and the later Wittgenstein, though I’d be hard-pressed to define exactly what I mean by that. Russell Goodman’s little book Wittgenstein and William James is interesting, but to my mind too much focused on the less interesting early work of both philosophers.]

But I should let Brown speak for himself; you’ll find more of his on his personal blog, Helmintholog (he wrote a book on nematode research a while back).

(I do beg Andrew Brown and the Guardian to forgive me for my rather extensive, nay, wholesale, quoting of this piece.)

How I lost my unfaith

When I started to write about religion I had no doubt that the future would be more secular and no less rational than the past I had grown up in. I was astonished to discover that there were still educated people who believed that St Paul had anything of interest to say about anything. It seemed obvious that they would fade away even within the church as they had faded outside. I thought that people who had learned about science could not take seriously the possibility of a world which was, as Carl Sagan put it, “demon-haunted”. I made my 13-year-old son read The Selfish Gene, and asked Richard Dawkins to sign his copy.

I suppose it’s 15 years since any of those hopes seemed plausible to me. Today, there are more people calling themselves atheists in the US than ever before, but superstition – as distinct from organised religion – is also a huge and growing business. Astrologers are the highest paid writers on Fleet Street. Creationism is just as absurd as it ever was, but much better funded. Globally, there have never been more believers alive than there are today, just as there have never been more slaves than in today’s world.

So it’s obvious that my earlier faith in the progress of reason was misplaced. The future may very well be more secular, but it won’t be any more rational without a tremendous moral effort — and any collective moral effort will have much of the characteristics of a religion, including a tendency to objectify and later to personify the abstractions by which we orient ourselves in world.

I still don’t for a moment believe in petitionary prayer or an intervening God; as I have said earlier; I don’t even think that the existence of God is a very interesting question. What has changed is what I believe about belief.

The trigger was two-fold. One was reading William James with real attention, but what had provoked that was rereading The Selfish Gene after a prolonged absence while I had been writing about religion. What that book said about biology seemed to me luminous and profound. What it said (in passing) about Christianity was palpable nonsense. I don’t mean here the opinion of God. I mean the description of faith, and of the psychology of belief.

No matter how often is it repeated that religious faith is uniquely and by definition a matter of assent to propositions for which there is no evidence, this simply won’t do as a description. Quite probably some or all forms of religion do involve assent to untrue propositions but so does any programme to change the world. So, for that matter, does belief in memes, or supposing that we, uniquely as a species, can overcome the tyranny of our selfish genes.

The subtle melancholy of Williams James, drifting like a fog into the bright certainties of his Victorian audience and quietly rusting them with doubt, was – and remains – much more realistic. James, in his Varieties of Religious Experience addressed head-on the paradox apparent even 120 years ago, that some people need to have faith to live at all even while everything they know about science suggests it is misplaced or wrong.

This isn’t the only form of religious belief, or even the most important one. The temperament that finds James attractive is not all that widespread. But he does — like Marx — locate the wellsprings of belief in the human heart. Nor does he suppose, as Marx did, that we could transcend the present limitations of our hearts in a revolutionary spasm of enlightenment.

We are all such helpless failures in the last resort.

He wrote:

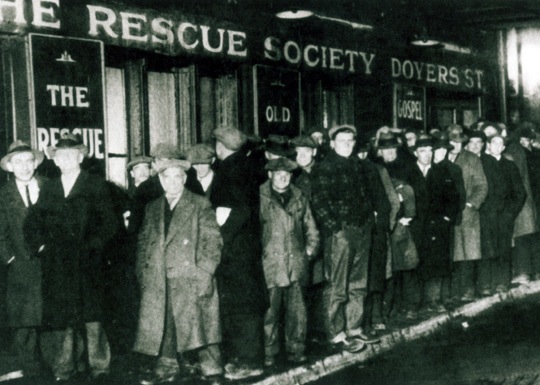

The sanest and best of us are of one clay with lunatics and prison inmates, and death finally runs the robustest of us down. And whenever we feel this, such a sense of the vanity and provisionality of our voluntary career comes over us that all our morality appears but as a plaster hiding a sore it can never cure, and all our well-doing as the hollowest substitute for that well being that our lives ought to be grounded in, but, alas! are not.

Now I submit that the only kind of atheist who does not feel like this sometimes is one who does not feel at all that they are one clay with the lunatics who believe; or else someone who, like Conrad in a letter of about the same period, feels confident enough in his own work not to care:

What makes mankind tragic is not that they are the victim of nature, it is that they are conscious of it. To be part of the animal kingdom under the conditions of this earth is very well – but as soon as you know of your slavery, the pain, the anger, the strife — the tragedy begins. We can’t return to nature since we can’t change our place in it. Our refuge is in stupidity, in drunkenness of all kinds, in lies, in beliefs, in murder, thieving, reforming — in negation, in contempt — each man according to the promptings of his particular devil. There is no morality, no knowledge, and no hope; there is only the consciousness of ourselves which drives us about a world that whether seen in a convex or a concave mirror, is always but a vain and fleeing appearance.

Both these grim visions are better and more cheerful than the religious prospect of eternal damnation. (I really do not think that anyone sane can contemplate steadily the Calvinist doctrine of eternal conscious torment.) But they are hardly cheerful ones, and they certainly don’t make one optimistic about a future of sunlit rationality.

Oddly enough, I think that James the psychologist was here more realistic about human nature than Conrad the novelist. Perhaps novelists can only make their points sidelong, by incarnation. But either way, when you carry the atheist programme to its conclusion, and naturalise religious belief, you are left with something which grows from the ineradicable desires of the human heart. Of course, a Buddhist might say it is our only hope to eradicate desire – but what is Buddhism but a religion itself?

I don’t doubt that it is possible to extinguish any particular theology and almost any religious community. But when they are gone, what stands in their place are different mythologies. William James was probably the father of the naturalistic study of religion: the psychology of religious experience is studiedly neutral as to the reality of whatever provoked these psychological experiences. But when the study of religion has been entirely naturalised, one of the things we can no longer do is to demonise believers. It may be that psychology tells us that we will continue to demonise our enemies whether or not we decently can: the trick has just proved too useful in the past. But in that case we will hardly have moved into a bright new world of rationality.