Thus Dean Baker.

The Bear Is Cool: Overcoming Fears of Falling Stock Prices

…

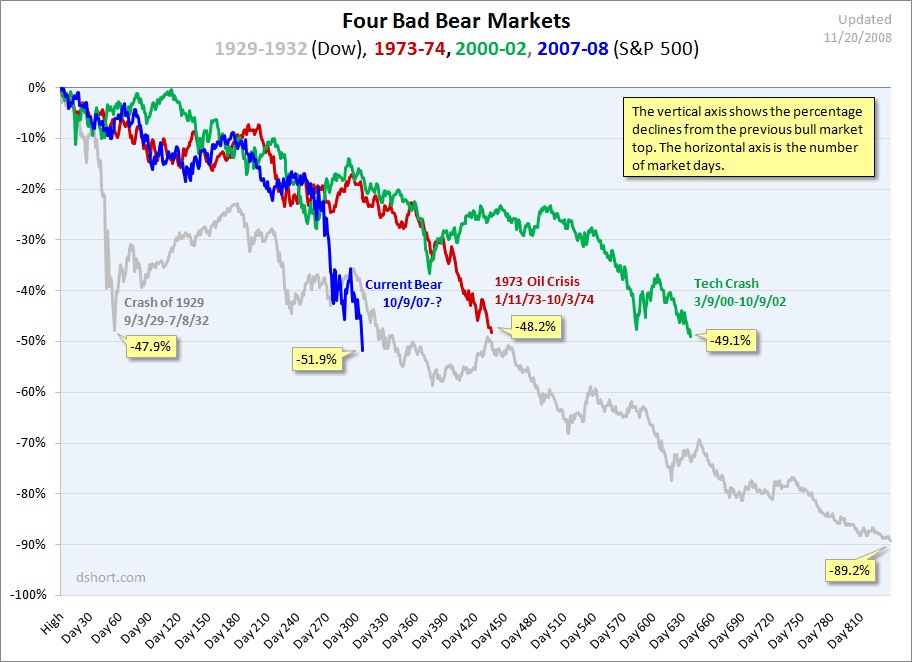

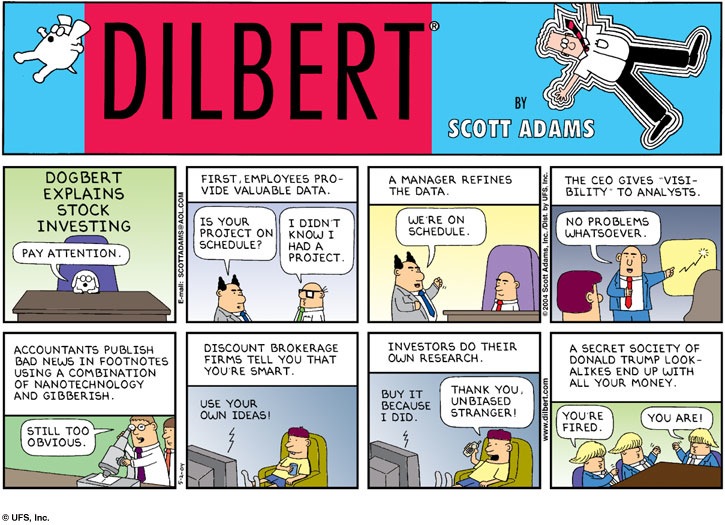

The economic data are indeed grim, but the plunge in stock prices need not be a major cause of concern to the bulk of us who have little or no stock. The basic story is that the stock market is paper wealth, just like bonds, dollar bills or other financial assets. The strength of the economy depends on its ability to produce goods and services, not sheets of paper.Even though the stock market has fallen by close to 50 percent, the economy still has the same capacity to produce computers and planes, to provide health care and education, and to develop new software and drugs. The economy is every bit as productive after the market collapse as it was before the collapse.

The plunge in stock prices destroyed paper wealth (lots of it). This is bad news for the relatively small group of people who had considerable stock wealth. However, for the bulk of the population, who own little or no stock, even including mutual funds in retirement accounts, the decline need not be cause for concern, since it has little direct impact on the economy.

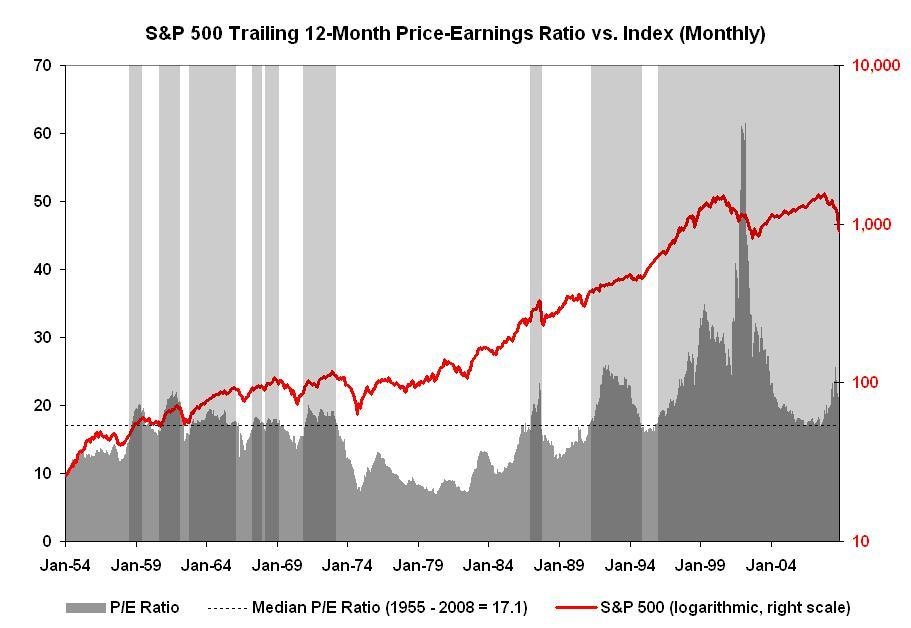

While there is a popular myth about firms selling stock to finance new investment, in reality the stock market has rarely been an important source of investment capital. Therefore, there is little reason to expect that the plunge in stock prices will have a substantial direct impact on investment or the economy.

There can be a substantial indirect impact of the plunge on the economy. People consume based in part on their stock wealth. Close to $10 trillion of stock wealth has been destroyed in the last year. This implies a falloff in annual consumption on the order of $300 to $400 billion. Unless this demand is replaced, it will amplify the drop in consumption resulting from the collapse of the housing bubble.

…

Unfortunately, the Bush administration refuses to take the economy’s plight seriously, but a large stimulus package will be the first agenda item of the new administration when it takes office in January. If President Obama commits the government to spending another $500 billion a year, or more if necessary, it can offset the loss in demand created by the fall in stock prices and the collapse of the housing bubble.Of course there will be other damage created by the loss of this stock wealth. Most importantly, the plunge in stock prices has left many public and private pension funds severely under-funded. The federal government can temporarily allow for somewhat more liberal accounting standards in the case of private funds and provide limited support for state and local governments trying to keep their funds solvent. We can ensure that retirees will receive the pensions they were promised.

There will be other people who will be hit by the loss of stock wealth, including tens of millions of workers with defined contribution retirement funds. This is unfortunate and points to the problem of the defined contribution pension system. Workers are forced to bear risk to an extent they probably did not recognize and almost certainly did not want.

One of the many items on the national agenda should be the repair of the private pension system so that all workers have access to a secure form of retirement savings. The plunge in value of retirement accounts should be a painful lesson to tens of millions of hard-working people that they should never trust Wall Street or the politicians it owns.

However, the most immediate story of the market crash is that it is a redistribution of wealth that goes overwhelmingly in the direction of the less wealthy. The plunge has destroyed claims to the nation’s wealth by the very wealthy in the same way that destroying $10 trillion in counterfeit bills held by mostly by the wealthy would destroy their wealth.

The key point going forward is to use government spending to ensure that demand remains strong. That way, the rest of the country need not suffer along with the formerly wealthy.