Here’s a pretty cool graph from Doug Short.

If that’s too depressing for you, follow the link for a slightly more optimistic version, based on a different inflation adjustment.

via The Big Picture

jonathan lundell

Economics broadly construed: macro, micro, behavioral, money, finance.

Here’s a pretty cool graph from Doug Short.

If that’s too depressing for you, follow the link for a slightly more optimistic version, based on a different inflation adjustment.

via The Big Picture

Uwe Reinhardt

If, like every university, the American Economic Association had a coat of arms, its obligatory Latin banner might read: “Est, ergo optimum est, dummodo ne gubernatio civitatis implicatur.” (“It exists, therefore it must be optimal, provided that government has not been involved.”)

The Economist says that this photo is "one of the most apt visual metaphors for the crisis yet". I’m not sure that it isn’t literally true. After all, Charlotte is a banking center, and 23 of the passengers worked at Bank of America alone. I’d say that the passengers in the 12 first-class seats at the front of the plane were disproportionately likely to be bankers, no?

Dean Baker:

Real Wages Soar and Nobody Notices

I enjoy reading about the hardships of Citigroup and Bank of America as much as anyone, but when the real wages of ordinary workers are soaring, it should merit at least some small bit of attention from the media. Since nominal wages have continued to increase in recent months, even as prices have plummeted, the real wage of workers lucky enough to keep their jobs has soared. …

I mainly wanted to post that first line (especially in view of my previous post); read the story to see why your wages might have been soaring while you weren’t paying attention.

Wow. Or, ouch.

Bespoke Investment Group notes that in less than two years, the market cap of the S&P financial sector has shrunk to $959 billion from nearly $3 trillion at its May 2007 peak.

Citigroup has lost in value close to 10 times its current market cap.

Source:

Parade of the Basket Cases

ALAN ABELSON

Barrons JANUARY 17, 2009

http://online.barrons.com/article/SB123215043364592063.html

Robert Reich.

What Should Be Done With The Next $350 Billion of Taxpayer Bailout: Criteria for TARP II

You may judge these conditions harsh. I think them prudent. They may force a number of big banks to go into chapter 11 bankruptcy, which would not be the end of the world but perhaps the beginning. At least then we’d find out what was on their balance sheets, because they’d have no choice but to sell off some of their junk, even at fire-sale prices (believe me, if the price is low enough, there are investors around the world who will buy them); they’d have to negotiate with their creditors and pay some of them off; many of their CEOs would be fired and directors replaced, which they should have been already; and most of their shareholders would be wiped out, which is unfortunate for them but, hey, they took the risk. In other words, these provisions would force the banks to clean up their balance sheets.

A useful reminder from Dean Baker: look behind the rhetoric. Cui bono?

The Money to “Save” Homeowners Is Handed to Banks

NPR reported on Representative Barney Frank’s effort to ensure that a substantial portion of the money from the second $350 billion in the TARP go toward helping homeowners. The proposals that purport to save homeowners would in fact hand large amounts of money to banks. They involve paying banks far above market prices for underwater mortgages. The benefit to homeowners is that they would be allowed to stay in their homes, possibly with zero equity. (Some proposals also give the homeowner a small equity cushion.)

NPR and other news outlets should be reporting who gets the money under these proposals. In many cases, banks may be paid tens of thousands of dollars to leave a homeowner in a home in which they have no equity. At a time when Congress is debating extending the State Children’s Health Insurance Program at a cost of $3,000 per kid, it is not clear how many kids’ health care they or the public would be willing to sacrifice to pay a bank to leave someone in a home in which they have no equity.

—Dean Baker

Mark Pittman at Bloomberg.

Paulson Bailout Didn’t Give Taxpayers Buffett’s Terms

Henry Paulson may be the most powerful manager of money in the world and he still couldn’t do for taxpayers with the $700 billion bailout of American banks what Warren Buffett did for his shareholders in investing in Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

The Treasury secretary has made 174 purchases of banks’ preferred shares that include certificates to buy stock at a later date. He invested $10 billion in Goldman Sachs in October, twice as much as Buffett did the month before, yet gained warrants worth one-fourth as much as the billionaire, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The Goldman Sachs terms were repeated in most of the other bank bailouts.

Paulson’s warrant deals may give U.S. taxpayers, who are funding the bailouts, less profit from any recovery in financial stocks than shareholders such as Goldman Sachs Chief Executive Officer Lloyd Blankfein and Saudi Arabian Prince Alwaleed bin Talal, owner of 4 percent of Citigroup Inc., said Simon Johnson, former chief economist for the International Monetary Fund.

The transactions are “just egregious,” said Johnson, a fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington. “You want to do it the way Warren does it.”

Paulson’s decisions mark the first time in the nation’s 236- year history that the U.S. government has had to prop up the financial system by purchasing shares in institutions from Goldman Sachs, the most profitable Wall Street firm last year, to Saigon National Bank, a Westminster, California, lender with a market value of $3.8 million.

…

via Barry Ritholtz

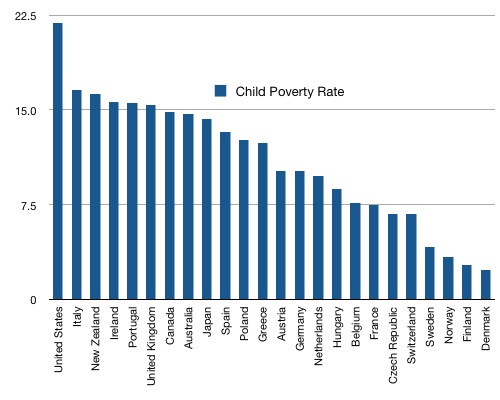

Matthew Yglesias wants to lower the threshold (that is, make it available to more families) for the Child Tax Credit, and adduces this evidence in support of the need to do so.

We’re #1!

No good reason, says Felix Salmon.

As SAR notes, the "longer and deeper recession" meme is "becoming the popular view" — it’s increasingly difficult to find people who really think we’ll bounce back in the second half of this year, and economists generally are much more bearish now than they were a couple of months ago.

So why is the stock market up 20% since then?

My feeling, mainstream as it may be, is that stocks are drifting upwards in blissful ignorance of reality, much as they did for nearly all of 2007, even after the credit crisis first hit. The panic sellers and the people desperately needing liquidity have left, volumes have fallen (as they always do around the holidays, no news there), and volatility has decreased. And so both value and momentum players are feeling increasingly comfortable rotating back in to the market.

…

The lesson of the past two years is that the stock market is a lagging, not a leading, indicator. I have no faith in this rally whatsoever; I hope that I’m wrong, but I just don’t see the current stock market reflecting an economy which is hugely reliant on retail spending and where holiday-season sales were the weakest in four decades. It’s always calmest before the storm, and I fear another gale might be brewing.

Dean Baker. The piece now has an addendum that explains Dean’s argument in a little more detail. Of course, this all depends on whether you “own large amounts of stock” or are “the rest of us”.

Wall Street’s Loss Can Be Our Gain

The lead article in the New Year’s Day edition of the Washington Post bemoaned the loss of $6.9 trillion in value in U.S. stock market last year. While those who own large amounts of stock have reason to shed tears, this may end being good news for the rest of us.

The loss of stock wealth means that stockholders have less claim to value of the country’s output. The U.S. economy can produce just as much in 2009 as it did in 2008 (in fact somewhat more, because of labor force and productivity growth). If stockholders can demand less because of the reduced value of their stock, then this leaves more for the rest of us. …

The Folks Who Told You the Economy Is Just Fine are Worried that the World Will Get Less Crowded

The last time I went to the beach it was very crowded. The Washington Post wants us to be concerned that it might be less crowded in 20 or 30 years. The problem is falling birth rates and declining populations.

That’s right the same people who told us a few months ago that the economy was just fine are now telling us that we should be worried about a planet with fewer people consuming less resources. Yes, this is yet another piece in the Post’s jihad against Social Security and Medicare.

A smaller population should make us richer, other things equal, since there will be less demand for beach space and other natural resources. The declining rate of workers to retirees can easily be met by productivity growth (a concept with which Post writers seem unfamiliar) and by losing a few jobs on the midnight shift at 7-11s.

The column warns us that China may grow old before its grows rich. At its recent growth rates, output per worker in China will be almost 6 times higher in twenty years as it is today. Suppose its ratio of retirees to workers doubles over this period. Then means that supporting retirees at current living standards would impose a burden on workers that is one-third as large (relative to their income) as the burden imposed at present. That should make everyone really scared.

—Dean Baker

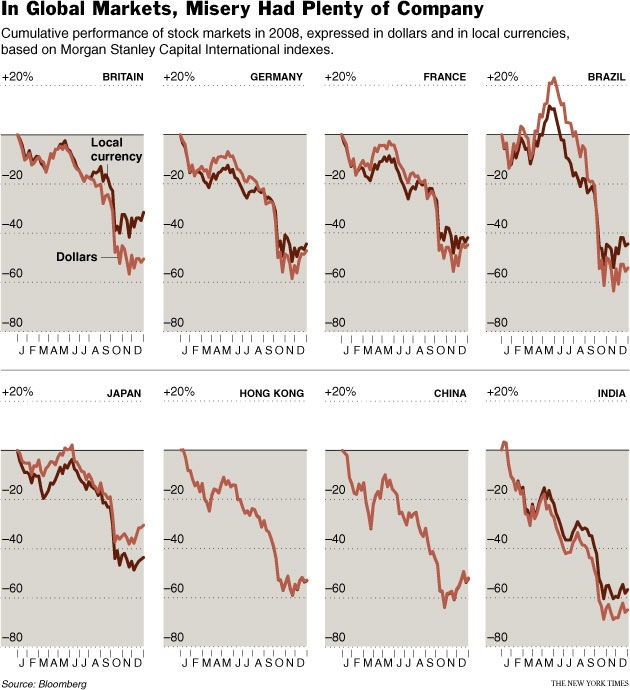

NY TImes via Barry Rithholtz.

Or are they just realists? Any more likely than anyone else to be right about 2009? Beats me.

New York Magazine again.

Nouriel Roubini

NYU business professor; chairman of RGE MonitorTRACK RECORD

Predicted this year’s crisis in 2006, pointing to a housing bust, oil shocks, and interest-rate increases.CURRENT PREDICTION

“It’s becoming a global recession. I expect it to be the worst U.S. recession of the last 50 years. I expect a cumulative fall in output from the peak of 4 percent and the unemployment rate going all the way to 9 percent.”

2008 Investment Guides Are HILARIOUS the New York Magazine. Of course, these folks are now giving advice for 2009—and being paid for it. A representative sample:

Jon Birger, senior writer, Fortune’s Investors Guide 2008

What he said then: “Question: What do you call it when an $8 billion asset write-down translates into a $30 billion loss in market cap? Answer: an overreaction … Smart investors should buy [Merrill Lynch] stock before everyone else comes to their senses.”

What we know now: Merrill agreed to sell itself Bank of America to avoid a Lehman-like flameout in a deal closing in January. Meanwhile, Merrill’s shares plummeted 77 percent.

via Barry Ritholtz

Abbreviated Dean Baker.

Challenging Group Thinking Economists on Budget Deficits and the Dollar

… In short, the economists who claim that the large budget deficits will lead to a fall in the value of the dollar have no more of clue than when they were denying the existence of a housing bubble two or three years ago. …

Joe Stiglitz this time.

The Dismal Economist’s Joyless Triumph

… The point of reciting these challenges facing the world is to suggest that, even if Obama and other world leaders do everything right, the US and the global economy are in for a difficult period. The question is not only how long the recession will last, but what the economy will look like when it emerges.

Will it return to robust growth, or will we have an anemic recovery, à la Japan in the 1990’s? Right now, I cast my vote for the latter, especially since the huge debt legacy is likely to dampen enthusiasm for the big stimulus that is required. Without a sufficiently large stimulus (in excess of 2 percent of GDP), we will have a vicious negative spiral: a weak economy will mean more bankruptcies, which will push stock prices down and interest rates up, undermine consumer confidence, and weaken banks. Consumption and investment will be cut back further.

Many Wall Street financiers, having received their gobs of cash, are returning to their fiscal religion of low deficits. It is remarkable how, having proven their incompetence, they are still revered in some quarters. What matters more than deficits is what we do with money; borrowing to finance high-productivity investments in education, technology, or infrastructure strengthens a nation’s balance sheet.

The financiers, however, will argue for caution: let’s see how the economy does, and if it needs more money, we can give it. But a firm that is forced into bankruptcy is not un-bankrupted when a course is reversed. The damage is long-lasting.

If Obama follows his instinct, pays attention to Main Street rather than Wall Street, and acts boldly, then there is a prospect that the economy will start to emerge from the downturn by late 2009. If not, the short-term prospects for America, and the world, are bleak.

Paul Krugman argues that mortgage rates should be (and have generally been) about a point and a half above 10-year Treasuries.

Mortgage rates are still too high

The persistence of the spread offers one opportunity for quick economic stimulus: declare that Fannie and Freddie are backed by full faith and credit, and if that doesn’t work, have the Treasury borrow on their behalf. This can bring mortgage rates down by more than 100 basis points. By itself, that’s not nearly enough to turn the economy around, but it could really help the economic recovery package.

The 10-year rate was 2.85% on Christmas Eve, down from 3.45% at the beginning of the month.

Matthew Yglesias explains compensation economics to Dean Baker.

The Washington Post takes a look at Fannie Mae’s new board. Dean Baker takes a look at the Post’s skewed priorities:

The remarkable part of this story is that the Washington Post reporter could not find a single person who thought that paying part-time workers $160,000 a year was a bad idea. There is absolutely no one cited in this piece who raised a question about the compensation levels for the board.

Keep in mind that this is a newspaper that is absolutely apoplectic over autoworkers getting $27 an hour. If we assume that the board members on average will devote 500 hours a year to their board duties, this puts their pay rate at $320 an hour.

Look, super-high salaries for the already wealthy equal necessary incentives for prosperity. Relatively high wages for the working class equals productivity destroying union malfeasance. That’s not really so hard to understand, is it?

The price of oil that is; thus Dave Cohen. I won’t try to summarize; the argument isn’t hard to follow, though.

Today’s NYMEX WTI oil price, about $45/barrel, is dangerously, outrageously low. Crude oil is not some “inconsequential penny stock” as Clive Maund pointed out, but that’s how it’s been priced (321Energy, November 19, 2008). I am going to talk about how oil prices get set in a futile attempt to understand what future prices might look like. I find little reason for optimism regarding the market’s ability to provide a coherent oil price signal reflecting future scarcity of this precious non-renewable resource.

Figure 1 is taken from James Hamilton’s Understanding Crude Oil Prices (UCSD Department of Economics, November 7, 2008); updated (in blue) to reflect the current price.

… The issue discussed in this essay is whether the price does or does not tell us about Our Oil Future. It does not. We know the $45 oil price is not right as we look down the road to a time when the global economy rises like a Phoenix from the ashes. Because of the nature of oil pricing, I find it likely that we revisit the 2008 nightmare over and over again in future years.

via James Hamilton