A quick note on theodicy | Andrew Brown

… No attempt to construct a rational calculus of suffering can succeed. …

Author: Jonathan

Robert Byrd crosses the bar

NPR’s Morning Edition concluded their remembrance of Robert Byrd with his reading of the end of Tennyson’s “Crossing the Bar”. The poem has never been one of my favorites, but it was a nice touch.

Sunset and evening star,

And one clear call for me!

And may there be no moaning of the bar,

When I put out to sea,But such a tide as moving seems asleep,

Too full for sound and foam,

When that which drew from out the boundless deep

Turns again home.Twilight and evening bell,

And after that the dark!

And may there be no sadness of farewell,

When I embark;For tho’ from out our bourne of Time and Place

The flood may bear me far,

I hope to see my Pilot face to face

When I have crossed the bar

What we want

From Juan Cole. As you can see from his title, this snippet is in the context of a longer McChrystal piece. But this is what jumped out at me.

Obama’s MacArthur Moment? McChrystal Disses Biden

… Obama has largely misunderstood the historical moment in the US. He appears to have thought that we wanted a broker, someone who could get everyone together and pull off a compromise that led to a deal among the parties. We don’t want that. We want Harry Truman. We want someone who will give them hell ….

Cause and effect in the War on Terror

Glenn Greenwald.

Cause and effect in the War on Terror

American discussions about what causes Terrorists to do what they do are typically conducted by ignoring the Terrorist’s explanation for why he does what he does. Yesterday, Faisal Shahzad pleaded guilty in a New York federal court to attempting to detonate a car bomb in Times Square, and this Pakistani-American Muslim explained why he transformed from a financial analyst living a law-abiding, middle-class American life into a Terrorist:

If the United States does not get out of Iraq, Afghanistan and other countries controlled by Muslims, he said, “we will be attacking U.S.,” adding that Americans “only care about their people, but they don’t care about the people elsewhere in the world when they die” . . . .

As soon as he was taken into custody May 3 at John F. Kennedy International Airport, onboard a flight to Dubai, the Pakistani-born Shahzad told agents that he was motivated by opposition to U.S. policy in the Muslim world, officials said.

“One of the first things he said was, ‘How would you feel if people attacked the United States? You are attacking a sovereign Pakistan’,” said one law enforcement official, who spoke on condition of anonymity because the interrogation reports are not public. “In the first two hours, he was talking about his desire to strike a blow against the United States for the cause.”

When the federal Judge presiding over his case asked him why he would be willing to kill civilians who have nothing to do with those actions, he replied: “Well, the people select the government. We consider them all the same” (the same rationale used to justify the punishment of the people of Gaza for electing Hamas). When the Judge interrupted him to ask whether that includes children who might have been killed by the bomb he planted and whether he first looked around to see if there were children nearby, Shahzad replied:

Well, the drone hits in Afghanistan and Iraq, they don’t see children, they don’t see anybody. They kill women, children, they kill everybody. It’s a war, and in war, they kill people. They’re killing all Muslims. . . .

I am part of the answer to the U.S. terrorizing the Muslim nations and the Muslim people. And, on behalf of that, I’m avenging the attack. Living in the United States, Americans only care about their own people, but they don’t care about the people elsewhere in the world when they die.

Those statements are consistent with a decade’s worth of emails and other private communications from Shahzad, as he railed with increasing fury against the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, drone attacks, Israeli violence against Palestinians and Muslims generally, Guantanamo and torture, and asked: “Can you tell me a way to save the oppressed? And a way to fight back when rockets are fired at us and Muslim blood flows?”

This proves only what it proves. The issue here is causation, not justification. The great contradiction of American foreign policy is that the very actions endlessly rationalized as necessary for combating Terrorism — invading, occupying and bombing other countries, limitless interference in the Muslim world, unconditional support for Israeli aggression, vast civil liberties abridgments such as torture, renditions, due-process-free imprisonments — are the very actions that fuel the anti-American hatred which, as the U.S. Government itself has long recognized, is what causes, fuels and exacerbates the Terrorism we’re ostensibly attempting to address.

It’s really quite simple: if we continue to bring violence to that part of the world, then that part of the world — and those who sympathize with it — will continue to want to bring violence to the U.S. Al Qaeda certainly recognizes that this is the case, as reflected in the statement it issued earlier this week citing the war in Afghanistan and support for Israel as its prime grievances against the U.S. Whether that’s what actually motivates that group’s leaders is not the issue. They are citing those policies because they know that those grievances resonate for many Muslims, who are willing to support radical groups and support or engage in violence only because they see it as retaliation or vengeance for the violence which the U.S. is continuously perpetrating in the Muslim world (speaking of which: this week, WikiLeaks will release numerous classified documents relating to a U.S. air strike in Garani, Afghanistan that killed scores of civilians last year, while new documents reveal that substantial amounts of U.S. spending in Afghanistan end up in the hands of corrupt warlords and Taliban commanders). Clearly, there are other factors (such as religious fanaticism) that drive some people to Terrorism, but for many, it is a causal reaction to what they perceive as unjust violence being brought to them by the United States.

Given all this, it should be anything but surprising that, as a new Pew poll reveals, there is a substantial drop in public support for both U.S. policies and Barack Obama personally in the Muslim world. In many Muslim countries, perceptions of the U.S. — which improved significantly upon Obama’s election — have now plummeted back to Bush-era levels, while Obama’s personal approval ratings, while still substantially higher than Bush’s, are also declining, in some cases precipitously. As Pew put it:

Roughly one year since Obama’s Cairo address, America’s image shows few signs of improving in the Muslim world, where opposition to key elements of U.S. foreign policy remains pervasive and many continue to perceive the U.S. as a potential military threat to their countries.

Gosh, where would they get that idea from? People generally don’t like it when their countries are invaded, bombed and occupied, when they’re detained without charges by a foreign power, when their internal politics are manipulated, when they see images of dead women and children as the result of remote-controlled robots from the sky. Some of them, after a breaking point is reached, get angry enough where they not only want to return the violence, but are willing to sacrifice their own lives to do so (just as was true for many Americans who enlisted after the one-day 9/11 attack). It’s one thing to argue that we should continue to do these things for geopolitical gain even it means incurring Terrorist attacks (and the endless civil liberties abridgments they engender); as amoral as that is, at least that’s a cogent thought. But to pretend that Terrorism simply occurs in a vacuum, that it’s mystifying why it happens, that it has nothing to do with U.S. actions in the Muslim world, requires intense self-delusion.

How much more evidence is needed for that?

* * * * *

Three other brief points illustrated by this Shahzad conviction: (1) yet again, civilian courts — i.e., real courts — provide far swifter and more certain punishment for Terrorists than do newly concocted military commissions; (2) Shahzad’s proclamation that he is a “Muslim soldier” fighting a “war” illustrates — yet again — that the way to fulfill the wishes of Terrorists (and promote their agenda) is to put them before a military commission or indefinitely detain them on the ground that they are “enemy combatants,” thus glorifying them as warriors rather than mere criminals (see this transcript of a federal judge denying shoe bomber Richard Reid’s deepest request to be treated as a “warrior” rather than a common criminal); and (3) the Supreme Court’s horrendous decision yesterday upholding the “material support” statute is, as David Cole explains, one of the most severe abridgments of First Amendment freedoms the Court has sanctified in a long time; this decision was justified by the need for courts to defer to executive and legislative branch determinations regarding “war,” proving once again that as long as this so-called “war” continues as a “war,” the abridgments on our core liberties will be as limitless as they are inevitable. At some point, we might want to factor that in to the cost-benefit analysis of our state of perpetual war (for more on yesterday’s Supreme Court ruling, see my podcast discussion from February with Shane Kadidal of the Center for Constitutional Rights, counsel to the plaintiffs in this case, on the day the Court heard Oral Argument, regarding the issues that case entailed).

The Facts Have A Well-Known Keynesian Bias

Paul Krugman:

The Facts Have A Well-Known Keynesian Bias

There are many things to say about Alan Greenspan’s op-ed yesterday, none of them complimentary. But what struck me is the passage highlighted by Tim Fernholz:

Despite the surge in federal debt to the public during the past 18 months—to $8.6 trillion from $5.5 trillion—inflation and long-term interest rates, the typical symptoms of fiscal excess, have remained remarkably subdued. This is regrettable, because it is fostering a sense of complacency that can have dire consequences.

You know, some people might take the fact that what’s actually happening is exactly what people like me were saying would happen — namely, that deficits in the face of a liquidity trap don’t drive up interest rates and don’t cause inflation — lends credence to the Keynesian view. But no: Greenspan KNOWS that deficits do these terrible things, and finds it “regrettable” that they aren’t actually happening. The triumph of prejudices over the evidence is a wondrous thing to behold. Unfortunately, millions of workers will pay the price for that triumph.

via Brad DeLong

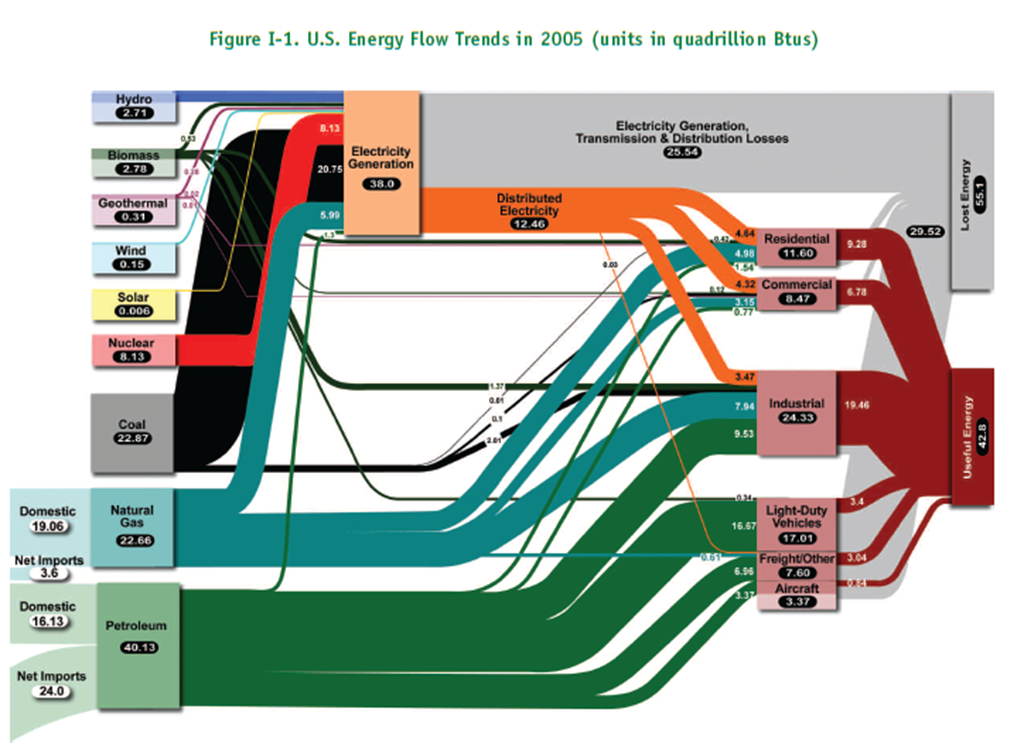

US Energy Flows

Via Ezra Klein.

Senate Moves to Keep 401(k) Fees Hidden

Just another reminder (not that you’ve forgotten) of who’s in charge here.

Senate Moves to Keep 401(k) Fees Hidden

Participants in 401(k) plans pay billions of dollars in fees — but most of them don’t know it. And the U.S. Senate apparently would like to keep it that way.

…

Paul Krugman’s War on Austerity

More to the previous point. This is Stephen Gandel, writing for The Curious Capitalist at TIME.com.

Paul Krugman’s War on Austerity

At a time when most people are saying the path out of the financial crisis and European debt problem is for individuals and governments around the world to cut back, Paul Krugman wants us to spend, spend, spend.

So how much we spend on supporting the economy in 2010 and 2011 is almost irrelevant to the fundamental budget picture. Why, then, are Very Serious People demanding immediate fiscal austerity?

The answer is, to reassure the markets — because the markets supposedly won’t believe in the willingness of governments to engage in long-run fiscal reform unless they inflict pointless pain right now. To repeat: the whole argument rests on the presumption that markets will turn on us unless we demonstrate a willingness to suffer, even though that suffering serves no purpose.

Krugman has of course been calling for additional stimulus spending for a while. So it may be easy to dismiss Krugman as a liberal who, despite his Nobel, is no longer in touch with economics. But he’s not the only one calling for more spending.

Besides Krugman, Martin Wolf of the Financial Times has been arguing against government cut backs in the wake of the economic slowdown as well.

This is all very well, many will respond, but what about the risks of a Greek-style meltdown? A year ago, I argued – in response to a vigorous public debate between the Harvard historian, Niall Ferguson, and the Nobel-laureate economist, Paul Krugman – that the rapid rise in US long-term interest rates was no more than a return to normal, after the panic. Subsequent developments strongly support this argument.

US government 10-year bond rates are a mere 3.2 per cent, down from 3.9 per cent on June 10 2009, Germany’s are 2.6 per cent, France’s 3 per cent and even the UK’s only 3.4 per cent. German rates are now where Japan’s were in early 1997, during the long slide from 7.9 per cent in 1990 to just above 1 per cent today. What about default risk? Markets seem to view that as close to zero. . . .

The question is whether such confidence will last. My guess – there is no certainty here – is that the US is more likely to be able to borrow for a long time, like Japan, than to be shut out of markets, like Greece, with the UK in-between.

The debate here is between about what we should care about more: The current state of the economy or a perception about the long-term state of the economy. Because right now it seems in our best interest to spend more money on jobs programs, extending unemployment benefits and other stimulus programs. The problem is that all of that additional spending along with the current roughly $1.5 trillion deficit is going to get us into trouble. Krugman comes down on the side of it is more important to worry about people suffering now. The Tea Partiers, and many economists, care more about what the spending now could to the welfare of our children.

The problem with this argument, as Wolf points out, is that the bond market doesn’t see the Armageddon that the Tea Partiers, gold hoarders and other see. The 10-year bond yield is at historic lows. Now you can make the argument that markets are irrational. Technology stocks and houses were not as safe as we thought. And that may be true about US bonds as well. And so to send this country further into debt just because there is currently some bullishness in the bond market is foolish. Here’s Tyler Cowen making that very point:

In the blogosphere, discussions of market constraints are too heavily influenced by interest rates, which also “measure” an ongoing flight to safety. (U.S. rates have fallen of late, but does that mean our fiscal position has improved? Hardly.) . . . . The real interest is only one indicator of where fiscal policy is at. The point that interest rates serve multiple functions, and don’t always communicate direct market information very well, comes from…John Maynard Keynes. Let’s at least keep that possibility in mind.

Yes, the bond market should tell us everything. You have to believe it tells us something. National economies are very large. And they can turn around very quickly. It’s not like our own personal economics. Getting out of credit card debt is very tough. Our incomes down change very much, and our spending patterns are ingrained in who we are. The US economy does surprising things. Who knew that Clinton was going to be able to get us into a surplus situation. Who would have guess that Bush would have been able to screw that up so quickly. And what about the financial crisis. Economies are very hard to predict. Interest rates even more so. So policy makers should go with what they know. We don’t know what our current deficits will mean for our children or even interest rates a year from now. We do know that people are unemployed and suffering financially. I say go with that.

Deja vu vu — epistemic relativism rides again

Not much posting recently, for various reasons; let’s see if we can do something about that.

Here’s a sample of an ongoing discussion of what I take to be the most critical issue, at least in the short to medium term, for the US economy. Paul Krugman has been the most visible and consistent proponent of more stimulus. When the original stimulus bill was passed, he argued strongly against dropping a big lump of aid to the states, and it’s pretty obvious now that he was right.

Many congressional Democrats are now running for the austerity hills, presumably in anticipation of the November elections. I doubt it’ll get them elected, but it’ll almost certainly screw the economy.

Deja vu vu — epistemic relativism rides again: What Happened To “What Works”?

by digby

So even the excuse for the Austerity Campaign is bullshit. Here’s Krugman:

Consider, if you will, the comparative cases of Ireland and Spain.

Both countries appeared, on the surface, to be fiscally responsible until the crisis hit, with balanced budgets and relatively low debt. Both discovered that this was an illusion: revenues were buoyed by immense real estate bubbles, and when the bubbles burst they plunged into deficit — and found themselves potentially on the hook for large bank losses.

The countries responded differently, however. Ireland quickly embraced harsh austerity; Spain has had to be dragged into austerity, and still faces major political unrest.

So, how’s it going? This article is typical of what you read: it describes the Irish as doing what has to be done, while the Spaniards dither. And it has good things to say about how the Irish response is working:

Much bitterness but also stoicism; markets impressed by Irish resolve to bite the austerity bullet.

Well, I guess that’s right — if by “markets impressed” you mean a CDS spread of 226 basis points, compared with 206 points for Spain; not to mention a 10-year bond rate of 5.11 percent, compared with 4.46 percent for Spain.

So, I’m glad to hear that Ireland’s stoic acceptance of austerity is reassuring markets; it must be true, because that’s what everyone says. Because if I didn’t know that, I might look at the data and conclude that markets actually have less confidence in Ireland than they do in Spain, and that austerity in the face of a deeply depressed economy doesn’t actually reassure markets at all.

But hey, what are you going to believe: what everyone knows, or your own lying eyes?

Everything’s Kabuki apparently, even this.

So, what’s really going on here? I’ve posited that it’s a Shock Doctrine move to take advantage of global economic insecurity to dismantle the welfare state. Krugman has said that he thinks part of it economists want to “appear tough.” Brad Delong thinks it might have to do with governing elites being too distant from the concerns of ordinary people. I think everyone agrees that this seems to have come up out of the blue and goes against what most experts assumed to be the accepted economic prescriptions for decades until now.

I feel as if we are watching a slow motion train wreck, mouths agape, powerless to do anything to stop it — the Very Serious People are all on board, assured in their own minds, for different reasons, that history has ended and nothing that came before can possibly be of any consequence.

In fact, I feel exactly the same way I felt in the lead up to the Iraq war.

James Galbraith: The danger posed by the deficit ‘is zero’

Ezra Klein – Galbraith: The danger posed by the deficit ‘is zero’

Galbraith: The danger posed by the deficit ‘is zero’

James Galbraith is an economist and the Lloyd M. Bentsen Jr. chair in government and business relations at the University of Texas at Austin. He’s also a skeptic of the prevailing concern over America’s long-term deficit. With many people now comparing America’s fiscal condition to Greece, I spoke with Galbraith to get the other side of the argument. An edited transcript of our conversation follows.

EK: You think the danger posed by the long-term deficit is overstated by most economists and economic commentators.

JG: No, I think the danger is zero. It’s not overstated. It’s completely misstated.

EK: Why?

JG: What is the nature of the danger? The only possible answer is that this larger deficit would cause a rise in the interest rate. Well, if the markets thought that was a serious risk, the rate on 20-year treasury bonds wouldn’t be 4 percent and change now. If the markets thought that the interest rate would be forced up by funding difficulties 10 year from now, it would show up in the 20-year rate. That rate has actually been coming down in the wake of the European crisis.

So there are two possibilities here. One is the theory is wrong. The other is that the market isn’t rational. And if the market isn’t rational, there’s no point in designing policy to accommodate the markets because you can’t accommodate an irrational entity.

…

Hand washing dispels the decision demons

Science, via Ars Technica. My interest in this stuff relates generally to how we strange creatures make decisions—voting, say.

Hand washing dispels the decision demons

According to an unusual study, washing your hands is not only healthy, but it may also put your mind at ease about recent past decisions. A couple of researchers at the University of Michigan conducted a study asking students to choose between two objects out of several they had ranked. When students washed their hands after making the choice, they seemed to experience less cognitive dissonance, while students who did not wash their hands behaved as if they needed to justify their choices to themselves.

People often try to justify choosing one thing, such what to eat, over another by convincing themselves that their choice is superior, even though both items seemed equally good a few seconds ago. This is our way of dispelling the cognitive dissonance choosing creates; if we don’t do this, we tend to fret about whether we decided correctly. A couple of researchers decided to test how this dissonance might be affected by the act of washing, which is sometimes linked with moral self-judgment, but hasn’t been tested much in relation to other psychological processes.

They set some college students about the task of choosing ten CDs for themselves out of a set of 30, and then ranking them in order of preference. For participating, students were offered a gift of their fifth- or sixth-choice CD. Next, the students were split in two groups— one group washed their hands, and the other just evaluated liquid soap packaging.

When the two groups re-ranked their ten CDs, students that did not wash their hands ranked the CD they chose higher, as if to indicate to themselves that they wanted that CD anyway. Students that did wash their hands, though, ranked their chosen CD about the same, showing that hand-washing somehow dispensed with the need to justify a choice.

The authors think this indicates that physical cleanliness may have a broader impact on individual psychology than previously thought—washing has been linked before to absolution of moral guilt, but less so to self-perception. The study was small and limited in scope, but if the link is real, we need hand wipes served with hot wings more than ever.

Magical voting

Is voting magical? | Andrew Brown

… So as a rational, self-interested actor, it makes no sense for me to vote. There is a reason why it’s important to tell us on election day that our votes will make a difference: thinking about it will lead the economically rational to conclude it’s not true. Nor did it make any sense for me to hold my nose. It was even more absurd than the enthusiasm of the football supporters in the pub last night, shouting in disappointment when their team missed a goal on television. They are least were taking part in a collective ritual with their friends; I was quite alone and unobserved.

One way of interpreting all these actions is as a form of sympathetic magic. While my rational mind knows perfectly well that neither my vote nor my pantomime will have any effect they are both behaviours that make sense only if on some level I do expect them to be effective. Similarly, the football fans surely believe that their support helps their team along – they behave as if they do, and still more as if the team was damaged by a lack of belief.

A more radical explanation is that the belief that we believe in magic is itself a rationalisation. Holding my nose while voting or shouting at an invisible football team is is entirely instinctive behaviour, and can be triggered even when it has no purpose at all, any more than giggling when I am tickled does, or sneezing when exposed to bright light. This is actually quite an important point in some theories of religion, like Pascal Boyer’s and one that is hard to answer: almost all our accounts of ritual behaviour are based on the idea that it is a conscious attempt to manipulate the world but maybe it is done entirely for its own sake. …

This is, after all, California

The Associated Press: Son of former Assembly speaker pleads guilty

Son of former Assembly speaker pleads guilty By JULIE WATSON (AP) — 4 hours ago SAN DIEGO — The son of former California state Assembly Speaker Fabian Nunez and another man pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter Wednesday in the fatal stabbing of a San Diego college student. …

C Compilers Disprove Fermat’s Last Theorem

This is from John Regehr, University of Utah. High wonk factor. You already know whether you’re interested; go with your instinct.

C Compilers Disprove Fermat’s Last Theorem

Obviously I’m not serious: compilers are bad at solving high-level math problems and also there is good reason to believe this theorem cannot be disproved. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Recently — for reasons that do not matter here — I wanted to write C code for an infinite loop, but where the compiler was not to understand that the loop was infinite. In contrast, if I had merely written

while (1) { } …

(via Danny Yee)

If the TSA Were Running New York

James Fallows.

If the TSA Were Running New York

How would it respond to this weekend’s Times Square bomb threat? Well, by extrapolation from its response to the 9/11 attacks and subsequent threats, the policy would be:

- All vans or SUVs headed into midtown Manhattan would have to stop and have their contents inspected. If any vehicle seemed for any reason to have escaped inspection, Midtown Manhattan in its entirety would be evacuated;

- A whole new uniformed force — the Times Square Security Administration, or TsSA – would be formed for this purpose;

- The restrictions would never be lifted and the TsSA would have permanent life, because the political incentives here work only one way. A politician who supports more permanent, more thorough, more expensive inspections can never be proven “wrong.” The absence of attacks shows that his measures have “worked”; and a new attack shows that inspections must go further still. A politician who wants to limit the inspections can never be proven “right.” An absence of attacks means that nothing has gone wrong — yet. Any future attack would always and forever be that politician’s “fault.” Given that asymmetry of risks, what public figure will ever be able to talk about paring back the TSA

…

Roger Ebert: Why I Hate 3-D Movies

Roger Ebert. This sounds just about right to me.

Roger Ebert: Why I Hate 3-D Movies

3-D is a waste of a perfectly good dimension. Hollywood’s current crazy stampede toward it is suicidal. It adds nothing essential to the moviegoing experience. For some, it is an annoying distraction. For others, it creates nausea and headaches. It is driven largely to sell expensive projection equipment and add a $5 to $7.50 surcharge on already expensive movie tickets. Its image is noticeably darker than standard 2-D. It is unsuitable for grown-up films of any seriousness. It limits the freedom of directors to make films as they choose. For moviegoers in the PG-13 and R ranges, it only rarely provides an experience worth paying a premium for.

…

Believe!

If you can. Sheesh. John Cole this time.

Talk about misreading the public mood. The Democratic immigration reform bill contains the following:

The national ID program would be titled the Believe System, an acronym for Biometric Enrollment, Locally stored Information and Electronic Verification of Employment.

It would require all workers across the nation to carry a card with a digital encryption key that would have to match work authorization databases.

“The cardholder’s identity will be verified by matching the biometric identifier stored within the microprocessing chip on the card to the identifier provided by the cardholder that shall be read by the scanner used by the employer,” states the Democratic legislative proposal.

The American Civil Liberties Union, a civil liberties defender often aligned with the Democratic Party, wasted no time in blasting the plan.

Apparently they think the outcry over the Arizona “SHOW YOUR PAPERS” bill is that it will only be applied to Hispanics. Polls pretty clearly demonstrate that half the country has no problem with the Arizona bill because it will not affect them- it only is an inconvenience for “others” (meaning brown people). But start talking about a national id with biometric data that everyone has to be issued, and you will think the death panels and health care reform debate were a walk in the park.

And I’m not even talking about the actual merits and downsides to the id card. I’m talking about the freak-out that will be inevitable, some of which I will probably even agree with. This is just stunningly tone deaf.

Democrats, Republicans just can’t quit Wall Street money

Ezra Klein. Just a reminder; I do hope that there’s nobody in the congregation today to whom this counts as news.

Democrats, Republicans just can’t quit Wall Street money

To think clearly about the overriding importance of money in campaigns, consider the degree to which politicians will court political disaster in order to raise a few more bucks. A couple of weeks ago, Mitch McConnell and John Cornyn took some time out of bashing bank bailouts to meet with a bunch of Wall Street executives. Democrats reacted with glee, and have hammered the Republicans for the meetings ever since. “McConnell won’t provide details of Wall Street meeting,” read one recent DNC press release.

And then you read this:

While Democrats push Wall Street regulations on the Senate floor, Banking Committee Chairman Chris Dodd (D-Conn.) and Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) will head to Manhattan on Monday for a fundraiser with deep-pocketed donors who have ties to the financial industry.

According to an invitation obtained by POLITICO, the fundraiser is billed as a “political discussion” for those who want to contribute up to $10,000 for Gillibrand’s reelection campaign and spend Monday evening with the two Democratic senators.

Democrats know exactly how politically dangerous it is to raise funds on Wall Street right now. But they’re doing it anyway. Both parties, in fact, know the risks and are choosing to take the hit rather than forgo the cash. This isn’t because they love being attacked or even think that the toxicity of Wall Street is overstated. It’s because, to use a metaphor that’s in vogue right now, our system of campaign finance turns politicians into vampire squids wrapped around the wallets of the rich, relentlessly jamming their blood funnels into anything that smells like money.

Does the Public Think that Drilling for Oil in Environmentally Sensitive Areas is an End In Itself?

Dean Baker. Of course.

Does the Public Think that Drilling for Oil in Environmentally Sensitive Areas is an End In Itself?

NPR told listeners that the public has supported drilling offshore because they objected to the country’s dependence on foreign oil and the wars in the Middle East.This is very interesting because it shows how badly the media have reported on this issue. There are no projections that show drilling offshore will have any noticeable effect on U.S. dependence on foreign oil. The media (including NPR) have horribly misrepresented the potential impact of offshore oil so that tens of millions of Americans actually believe that it has anything to do with dependence on foreign oil.

It would have been interesting to report the attitudes towards offshore drilling among those who know that it will not have any noticeable impact on U.S. dependence on foreign oil or the price of gas.

R G Collingwood

Andrew Brown points us to Simon Blackburn’s review in The New Republic of a new biography of R G Collingwood, quoting along the way this admiration.

“Although art as magic is not art proper, Collingwood accords it the greatest respect. He dismisses more brutally and contemptuously even than Wittgenstein the patronizing view, held by Frazer, Lévy-Bruhl, and other anthropologists of his time, that religion and magic simply amount to bad science, so that the “savage mind” is one lacking the most elementary knowledge of cause and effect. He also dismisses the ludicrous Freudian view that magic is a kind of neurosis in which the patient supposes that by wishing for a thing he can bring it about. Instead, Collingwood insists, surely correctly, that the end of magic is the raising and channeling of emotion: ‘magical activity is a kind of dynamo supplying the mechanism of practical life with the current that drives it.’ Its true purpose is not, say, to avert natural catastrophes, but to ‘produce in men an emotional state of willingness to bear them with fortitude and hope.’

“This attitude gave Collingwood an uncommon sympathy with religious ritual and practice, and a much more realistic understanding of its ongoing place in human life. He also enables us to see why the majority of people, including those like myself who have no religious attachments, are nevertheless embarrassed at the dogmatic contempt poured on religious practice by our more militant atheists. Every sane person recognizes at some level that dance, music, poetry, and ritual may be just what you need as you prepare to face a battle, or desolation, failure, grief, or death.”

Blackburn isn’t uncritical, though.

If Collingwood is as acute and interesting as I have suggested, how does it happen that he is largely a minority interest? He has his devotees, certainly; but I doubt if he is more than a ghost in the footnotes to syllabi across the Western world. The comparison to Wittgenstein might help. It is difficult to pick up a page of Wittgenstein without being seduced: whether you understand it or not, the sense is overwhelming that something of the highest importance is being addressed with a rare detachment and intelligence. With Collingwood, there is assertion and bravado instead of seduction. Wittgenstein shows that he is a wonderfully and originally reflective thinker; Collingwood cannot help telling you that he is. Wittgenstein is silent about his being capable of other things as well; Collingwood boasts of it. You can read all of Wittgenstein without knowing of his genuine heroism during World War I. One cannot help feeling that had Collingwood done anything like that, it would have cropped up on every other page. All this is off-putting, and Collingwood’s readers have to learn to shake their heads with a smile rather than toss the whole thing into the bin.