Rotwang at TPM. The paper in question was co-authored by Dean Baker, Brad DeLong, and Paul Krugman.

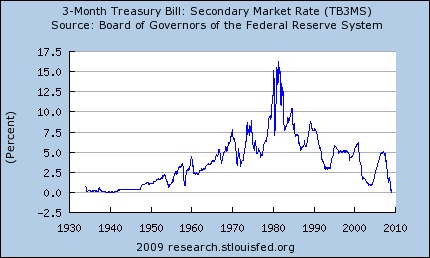

… My one-sentence summary of the paper is that the stock market can’t possibly be as good a long-run investment, relative to Social Security, as is commonly thrown about. At the time this was controversial. By ‘good’ I mean having a desirable mixture of low risk and decent return. As everyone should know, there is a trade-off between the two (risk & return, that is).

The average growth rate of the U.S. economy has been somewhere between three and four percent, after deducting inflation. Growth is a creature of growing labor supply, additions to the capital stock, and occasional hiccups (both positive and negative) from technological progress and who knows what else. In my view it is not well understood by economists. (I suspect I will not have to work hard to persuade you of that.) At any rate, in advanced industrial countries you would be foolish to expect sustained growth above five percent.

Even these numbers have an illusory component, since they do not account for depletion of the natural environment, the exhaustion of leisure time, and the sacrifice of other non-market amenities.

So it is idiotic to expect stocks to grow at double digit rates. In terms of ‘fundamentals,’ the value of stocks depends on the growth of profits from productive activity. Firms produce stuff that people want to buy. When you buy a stock you are buying an uncertain stream of future income. Some of this you may get in the form of cash dividends, otherwise you may reap capital gains. Alternatively, when you buy a bond you are buying a guaranteed share of a company’s profits, but the company’s survival is itself uncertain. Either way, you can’t expect double digit returns on average for any sustained period of time.

Everything else is buying or selling in expectation of a short-term run-up or drop, respectively, in price, otherwise known as speculation. Your gain will be somebody else’s loss, and vice versa. A huge accumulation of gains will end up as a big loss at some point. You can be lucky with a particular stock or with a particular portfolio for a particular period of time. You can be unlucky too.

…

Before I start shredding “

Before I start shredding “

Background: In a NY Times

Background: In a NY Times