Simon Johnson has a terrific article at The Atlantic Online. It’s long and worth reading. I’m still working my way through it, but I thought I’d post a couple of short bits along with the link.

The Quiet Coup

… But I must tell you, to IMF officials, all of these crises looked depressingly similar. Each country, of course, needed a loan, but more than that, each needed to make big changes so that the loan could really work. Almost always, countries in crisis need to learn to live within their means after a period of excess—exports must be increased, and imports cut—and the goal is to do this without the most horrible of recessions. Naturally, the fund’s economists spend time figuring out the policies—budget, money supply, and the like—that make sense in this context. Yet the economic solution is seldom very hard to work out.

No, the real concern of the fund’s senior staff, and the biggest obstacle to recovery, is almost invariably the politics of countries in crisis.

Typically, these countries are in a desperate economic situation for one simple reason—the powerful elites within them overreached in good times and took too many risks. Emerging-market governments and their private-sector allies commonly form a tight-knit—and, most of the time, genteel—oligarchy, running the country rather like a profit-seeking company in which they are the controlling shareholders. When a country like Indonesia or South Korea or Russia grows, so do the ambitions of its captains of industry. As masters of their mini-universe, these people make some investments that clearly benefit the broader economy, but they also start making bigger and riskier bets. They reckon—correctly, in most cases—that their political connections will allow them to push onto the government any substantial problems that arise.

In Russia, for instance, the private sector is now in serious trouble because, over the past five years or so, it borrowed at least $490 billion from global banks and investors on the assumption that the country’s energy sector could support a permanent increase in consumption throughout the economy. As Russia’s oligarchs spent this capital, acquiring other companies and embarking on ambitious investment plans that generated jobs, their importance to the political elite increased. Growing political support meant better access to lucrative contracts, tax breaks, and subsidies. And foreign investors could not have been more pleased; all other things being equal, they prefer to lend money to people who have the implicit backing of their national governments, even if that backing gives off the faint whiff of corruption.

But inevitably, emerging-market oligarchs get carried away; they waste money and build massive business empires on a mountain of debt. Local banks, sometimes pressured by the government, become too willing to extend credit to the elite and to those who depend on them. Overborrowing always ends badly, whether for an individual, a company, or a country. Sooner or later, credit conditions become tighter and no one will lend you money on anything close to affordable terms.

The downward spiral that follows is remarkably steep. Enormous companies teeter on the brink of default, and the local banks that have lent to them collapse. Yesterday’s “public-private partnerships” are relabeled “crony capitalism.” With credit unavailable, economic paralysis ensues, and conditions just get worse and worse. The government is forced to draw down its foreign-currency reserves to pay for imports, service debt, and cover private losses. But these reserves will eventually run out. If the country cannot right itself before that happens, it will default on its sovereign debt and become an economic pariah. The government, in its race to stop the bleeding, will typically need to wipe out some of the national champions—now hemorrhaging cash—and usually restructure a banking system that’s gone badly out of balance. It will, in other words, need to squeeze at least some of its oligarchs.

Squeezing the oligarchs, though, is seldom the strategy of choice among emerging-market governments. Quite the contrary: at the outset of the crisis, the oligarchs are usually among the first to get extra help from the government, such as preferential access to foreign currency, or maybe a nice tax break, or—here’s a classic Kremlin bailout technique—the assumption of private debt obligations by the government. Under duress, generosity toward old friends takes many innovative forms. Meanwhile, needing to squeeze someone, most emerging-market governments look first to ordinary working folk—at least until the riots grow too large.

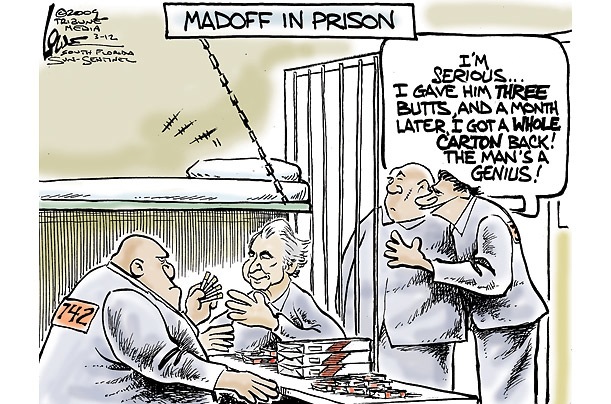

Eventually, as the oligarchs in Putin’s Russia now realize, some within the elite have to lose out before recovery can begin. It’s a game of musical chairs: there just aren’t enough currency reserves to take care of everyone, and the government cannot afford to take over private-sector debt completely.

So the IMF staff looks into the eyes of the minister of finance and decides whether the government is serious yet. The fund will give even a country like Russia a loan eventually, but first it wants to make sure Prime Minister Putin is ready, willing, and able to be tough on some of his friends. If he is not ready to throw former pals to the wolves, the fund can wait. And when he is ready, the fund is happy to make helpful suggestions—particularly with regard to wresting control of the banking system from the hands of the most incompetent and avaricious “entrepreneurs.”

Of course, Putin’s ex-friends will fight back. They’ll mobilize allies, work the system, and put pressure on other parts of the government to get additional subsidies. In extreme cases, they’ll even try subversion—including calling up their contacts in the American foreign-policy establishment, as the Ukrainians did with some success in the late 1990s. …

Well, you can see where this is going. Pay attention, now.

Johnson is not exactly optimistic.

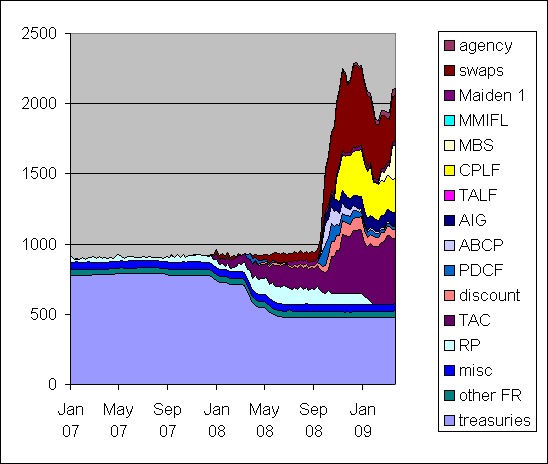

Johnson is no wild-eyed prophet of doom. While the Fed and the US Treasury are being operated by Johnson’s elites, or at least their BFFs, we can see that those folks are no less concerned. Here’s a graph of Fed lending for the last couple of years, from a longer posting by Mark Thoma (also worth reading):

That’s trillions of dollars being pushed into reserves. This is not business as usual.

In the movie Lars and the Real Girl, the main character imagines that a female blow-up doll is his fiancée. To humor Lars, his brother and sister-in-law go along with the charade. Over the course of the movie, more people are drawn into the circle, until eventually the whole town is treating Bianca the blow-up doll as one of its leading citizens. …

In the movie Lars and the Real Girl, the main character imagines that a female blow-up doll is his fiancée. To humor Lars, his brother and sister-in-law go along with the charade. Over the course of the movie, more people are drawn into the circle, until eventually the whole town is treating Bianca the blow-up doll as one of its leading citizens. … … In essence, Paulson and his cronies turned the federal government into one gigantic, half-opaque holding company, one whose balance sheet includes the world’s most appallingly large and risky hedge fund, a controlling stake in a dying insurance giant, huge investments in a group of teetering megabanks, and shares here and there in various auto-finance companies, student loans, and other failing businesses. Like AIG, this new federal holding company is a firm that has no mechanism for auditing itself and is run by leaders who have very little grasp of the daily operations of its disparate subsidiary operations.

… In essence, Paulson and his cronies turned the federal government into one gigantic, half-opaque holding company, one whose balance sheet includes the world’s most appallingly large and risky hedge fund, a controlling stake in a dying insurance giant, huge investments in a group of teetering megabanks, and shares here and there in various auto-finance companies, student loans, and other failing businesses. Like AIG, this new federal holding company is a firm that has no mechanism for auditing itself and is run by leaders who have very little grasp of the daily operations of its disparate subsidiary operations.