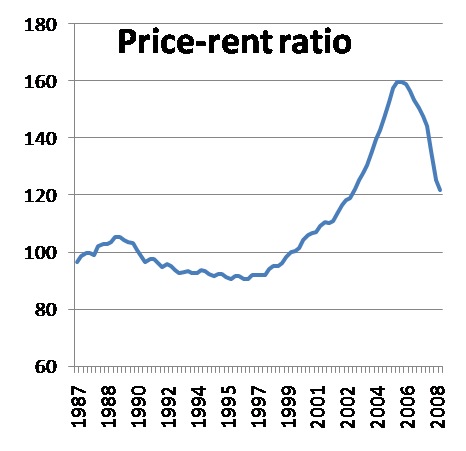

Paul Krugman this time (that’s housing price/rent).

jonathan lundell

Economics broadly construed: macro, micro, behavioral, money, finance.

Paul Krugman this time (that’s housing price/rent).

Via Brad DeLong.

Reporters on economics and business should know that, but from the reporting on the bailout, it is clear that very few do. There seems to be a view that stock market wealth is money from heaven.

Ownership of stock is a claim to the future profits of the corporations whose stock is owned. If the value of stocks increase because the economy is expected to grow more rapidly, and therefore future profits will be larger, then it is reasonable to say that a higher stock market is good news for everyone.

But suppose the stock market goes up because the markets think that the government will tax school teachers and fire fighters to hand money to Wall Street banks. Is this one good for everyone?

Finally, suppose that the Wall Street titans haven’t a clue what future profits will be (these are the folks that pushed the NASDAQ above 5000), and a rise in the stock market is driven by irrational exuberance. In this case, the higher stock market simply means that stockholders have a greater claim on the same amount of national wealth. This would be like handing out a trillion dollar bills and giving them only to shareholders. That’s good for the shareholders, but not for the rest of the country.

It would be nice if the folks who report the news understood that the stock market is not the economy.

—Dean Baker

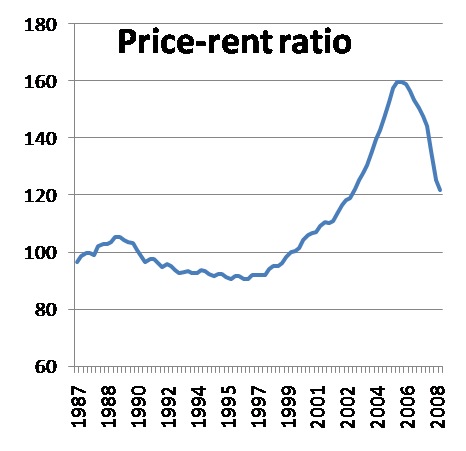

Barry Ritholtz points us to this nifty graphic, courtesy of the NY Times (click image for bigger version).

(Via The Big Picture)

Seems I’m not doing anything but quoting Dean Baker. So be it.

Pets.Com Is Not Coming Back and House Prices Will NOT Recover!

There are numerous accounts of the bailout that discuss the possibility that taxpayers will make money on the deal when the housing market stabilizes (e.g. the print version of the Post article). This is a fairy tale.

We had a housing bubble. A housing bubble is like a stock bubble. Prices get over-valued because of irrational exuberance and do not reflect fundamentals. After the bubble collapses, prices fall back to levels consistent with their fundamentals.

In the current case, the bubble is about half deflated and house prices are falling rapidly. They are not falling because of the credit crisis. They are falling because of an enormous over-supply of housing. The vacancy rate for ownership units was already 50 percent higher than its previous record in the fall of 2006. This was before there was any credit crunch.

The fact that Alan Greenspan, Henry Paulson, Ben Bernanke and many other others in positions of authority did not recognize the housing the housing bubble in years from 2004-2006 demonstrated extraordinary incompetence. Anyone who still does not understand that the root problem is a bursting housing bubble should not be allowed near the negotiations and certainly should not be writing news articles trying to inform the public.

–Dean Baker

Let’s just quote Dean Baker, shall we? (If the apparent date of the post is correct, this went up early Monday morning, before the House voted the bailout bill down.

Why Bail? The Banks Have a Gun Pointed at Their Head and Are Threatening to Pull the Trigger

If you have a real story, you don’t have to make up phony stories. That’s pretty straightforward.

I’ve heard lots of phony stories. Much of the country’s political and economic leadership has been running around raising the prospect of the Great Depression and a breakdown in the banking system (I actually had taken the latter seriously). These stories are absolutely not true.

There is no plausible scenario under which the no bailout scenario gives us a Great Depression. There is a more plausible scenario (but highly unlikely) that the bailout will give us a Great Depression. There is no way that the failure to do a bailout will lead to more than a very brief failure of the financial system. We will not lose our modern system of payments.

At this point I cannot identify a single good reason to do the bailout.

The basic argument for the bailout is that the banks are filled with so much bad debt that the banks can’t trust each other to repay loans. This creates a situation in which the system of payments breaks down. That would mean that we cannot use our ATMs or credit cards or cash checks.

That is a very frightening scenario, but this is not where things end. The Federal Reserve Board would surely step in and take over the major money center banks so that the system of payments would begin functioning again. The Fed was prepared to take over the major banks back in the 80s when bad debt to developing countries threatened to make them insolvent. It is inconceivable that it has not made similar preparations in the current crisis.

In other words, the worst case scenario is that we have an extremely scary day in which the markets freeze for a few hours. Then the Fed steps in and takes over the major banks. The system of payments continues to operate exactly as before, but the bank executives are out of their jobs and the bank shareholders have likely lost most of their money. In other words, the banks have a gun pointed to their heads and are threatening to pull the trigger unless we hand them $700 billion.

If we are not worried about this worst case scenario (to be clear, I wouldn’t want to see it), then why should we do the bailout?

There has been a mountain of scare stories and misinformation circulated to push the bailout. Yes, banks have tightened credit. Yes, we are in a recession. But the problem is not a freeze up of the banking system. The problem is the collapse of an $8 trillion housing bubble. (It was remarkable how many so-called experts somehow could not see the housing bubble as it grew to ever more dangerous levels. It is even more remarkable that many of these experts still don’t recognize the bubble even as its collapse sinks the economy and the financial system.) The decline in housing prices to date has already cost the economy $4 trillion to $5 trillion in housing equity. This would be expected to lead to a decline in annual consumption on the order of $160 billion to $300 billion.

Given the loss of housing equity, I have actually been surprised that the downturn has not been sharper. Homeowners had been consuming based on their home equity. Much of that equity has now disappeared with the collapse of the bubble. We would expect that their consumption would fall. We also would expect that banks would be reluctant to lend to people who no longer have any collateral.

This is the story of the downturn and of course the bailout does almost nothing to counter this drop in demand. At best, it will make capital available to some marginal lenders who would not otherwise receive loans. We should demand more for $700 billion.

For the record, the restrictions on executive pay and the commitment to give the taxpayers equity in banks in exchange for buying bad assets are jokes. These provisions are sops to provide cover. They are not written in ways to be binding. (And Congress knows how to write binding rules.)

Finally, the bailout absolutely can make things worse. We are going to be in a serious recession because of the collapse of the housing bubble. We will need effective stimulus measures to boost the economy and keep the recession from getting worse.

However, the $700 billion outlay on the bailout is likely to be used as an argument against effective stimulus. We have already seen voices like the Washington Post and the Wall Street funded Peterson Foundation arguing that the government will have to make serious cutbacks because of the bailout.

While their argument is wrong, these are powerful voices in national debates. If the bailout proves to be an obstacle to effective stimulus in future months and years, then the bailout could lead to exactly the sort of prolonged economic downturn that its proponents claim it is intended to prevent.

In short, the bailout rewards some of the richest people in the country for their incompetence. It provides little obvious economic benefit and could lead to long-term harm. That looks like a pretty bad deal.

At a Harvard panel discussion [video] yesterday, economics professor Ken Rogoff made an interesting point: The liquidity crisis isn’t real. Or, to restate it: Any liquidity crisis is caused by the promise of a government bailout. Ken said that his many friends in investment banking said that there is plenty of money to invest in financial services, but right now it is “sitting on the sidelines.” Why? Because the financial services industry does not want to pay the terms demanded. As he put it, why do business with Warren Buffett who will negotiate a tough deal, if you believe that the government will ride in soon with cheaper cash?

Ken also talked about the need to shrink the financial services sector. He thinks it is good that the investment banking houses are failing and many people on Wall Street are losing their jobs because, in his view, we have an oversupply in that sector and our economy just can’t support it.Ken’s background with the IMF and on the Board of the Federal Reserve add a certain credibility to his assessment of conditions on Wall Street. If he is right, the $700 bailout is saving some investment bankers’ jobs in the short term, but overall it is making the financial system worse.

It was a terrific panel: Nobel winner Robert Merton, Dean of the Harvard Business School Jay Light, Harvard economist and Chair of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers-2003-05 Greg Mankiw, Harvard Business School Prof and long-time Goldman Sachs partner Robert Kaplan, and me*. It might be worth listening to the webcast.

If you tune in, don’t miss Ken’s talk (he is fifth of the six of us). He is calm and funny, but there is no too-big-to-fail talk. Instead, he makes the whole rush-to-bailout look like a very bad idea.

* “me” being Elizabeth Warren, Leo Gottlieb Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, the other standout participant on the panel.

* “me” being Elizabeth Warren, Leo Gottlieb Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, the other standout participant on the panel.

You may not have the interest or patience for this; it’s about an hour and a half long, and not every participant is quite as lucid as Rogoff and Warren. But if you do, I think you’ll find it rewarding, especially Warren’s own contribution on the roots of the current Wall Street troubles in the anything-goes mortgage market of the housing bubble.

Bonus link: Wikipedia has a decent article on credit default swaps (described briefly by one of the panelists), in which it appears that they’re every bit as insane as they sound.

Last week the SF Chronicle published a story describing two subprime mortgages written in San Francisco by Lehman Brothers subsidiary BNC Mortgage.

One homeowner, Johnny Pitts, was a Muni bus driver who had bought an Oakland home for $429,950 in 2005. His mortgage payment, which had started at $2,880, was about to reset to $3,730 a month – plus $750 more for taxes and insurance. Home payments are supposed to be no more than 40 percent of income. By that formula, the necessary income would have been $11,200 a month or $134,400 a year. Was it reasonable to assume a bus driver was bringing home that kind of money? In fact, Pitts’s take-home pay was just $4,000 a month.

Loans both 100 percent

The other homeowners, Jeff and Vanessa Hahn of Fairfield, were on the hook for monthly payments of $5,000 – exactly the amount they earned together as a self-employed businessman and teacher.

As for loan to value, in both cases it was 100 percent – hardly a desirable ratio. Pitts had a piggyback second loan; together the two loans accounted for the full purchase price. The Hahns had done a cash-out refinance for their home’s full assessed value of $570,000 in March 2007, a few months before the article was written.

And the values themselves were questionable. Within months, both homes were worth about $100,000 less than the loans – but based on that rapid rate of decline it seemed likely they had been worth less even when the mortgages were written.

Lehman is gone, of course, but it’s hard to believe that they were very much the exception.

This is part of the background to the current bail-out talks.

Bonus: Lehman’s mission statement:

We are one firm, defined by our unwavering commitment to our clients, our shareholders, and each other. Our mission is to build unrivaled partnerships with and value for our clients, through the knowledge, creativity, and dedication of our people, leading to superior returns to our shareholders.

Now this is reassuring.

Bad News For The Bailout — Forbes.com

In fact, some of the most basic details, including the $700 billion figure Treasury would use to buy up bad debt, are fuzzy.

“It’s not based on any particular data point,” a Treasury spokeswoman told Forbes.com Tuesday. “We just wanted to choose a really large number.”

The New York Times printed this piece on credit default swaps, which have been in the news quite a bit recently. The basic idea is fairly simple, but the ramifications give me a headache. You can have one too.

Arcane Market Is Next to Face Big Credit Test

Credit default swaps form a large but obscure market that will be put to its first big test as a looming economic downturn strains companies’ finances. Like a homeowner’s policy that insures against a flood or fire, these instruments are intended to cover losses to banks and bondholders when companies fail to pay their debts.

The market for these securities is enormous. Since 2000, it has ballooned from $900 billion to more than $45.5 trillion — roughly twice the size of the entire United States stock market.

No one knows how troubled the credit swaps market is, because, like the now-distressed market for subprime mortgage securities, it is unregulated. But because swaps have proliferated so rapidly, experts say that a hiccup in this market could set off a chain reaction of losses at financial institutions, making it even harder for borrowers to get loans that grease economic activity.

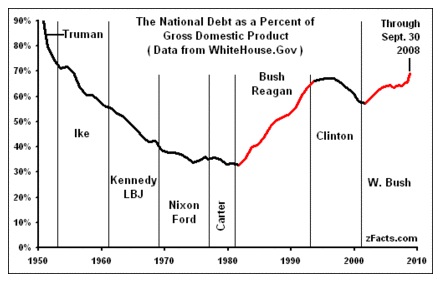

This chart is not seasonally adjusted, so it’s hard (impossible) to see month-to-month trends. But the annual trend is certainly dramatic. The crash starts in April 2006 and never looks back.

Calculated Risk via Barry Ritholtz

Update: here’s a companion graph (on a much longer time scale) of real housing prices from Matthew Yglesias. Not surprisingly, the price crash starts just about when the volume starts to drop.

Thus Dean Baker.

Leonhardt is Wrong, Limiting CEO Pay is Not a Sideshow to This Bailout

In his weekly NYT column, David Leonhardt argues that limits on executive compensation are a sideshow to the bank bailout. Actually, they are an essential part of the story.

A key issue in the bailout is addressing moral hazard. The message to Wall Street should not be to get rich on fees from stupid loans and then run to the big government to save your rear when the loans go bad. We give this message to the shareholders by saying that we are going to own much or all of your bank if you come to us for help.

It is necessary to give a similar lesson to the CEOs. A major problem in corporate America is that top executives have been able to pillage their corporations at the expense of shareholders. This problem is nowhere worse than on Wall Street, where high level executives (not just CEOs) routinely earn tens of millions annually in compensation, and sometimes hundreds of millions.

It is therefore crucial that the CEOs also be forced to take big hits in this sort of bailout. Otherwise, their incentive is to rip off their shareholders in the good times with irresponsible lending policies (thereby getting huge fees) and then have the government kick the shareholders in the teeth in the bad times, but they themselves can escape unscathed.

In short, kicking the top management in the teeth as part of the bailout is both a necessary part of the bailout and good policy for stemming the growth in inequality over the last three decades.

—Dean Baker

I am having a hard time keeping up with all of the bailouts and special facilities created for dealing with this crisis. Am I missing any?

- Bear Stearns

- Economic Stimulus progam

- Housing Bailout Program

- Fannie & Freddie

- AIG

- No Short selling rules

- Fed liquidity programs (Term Lending facility, Term Auction facility)

- Money Market fund insurance program

- New RTC type program

If you are a fan of irony, consider this: The conservative movement has utterly hated FDR, and his New Deal programs like Medicaid, Social Security, FDIC, Fannie Mae (1938), and the SEC for nearly 80 years. And for the past 8 years, a conservative was in the White House, with a very conservative agenda. For something like 16 of the past 18 years, the conservative dominated GOP has controlled Congress.

Those are the facts.

We now see that the grand experiment of deregulation has ended, and ended badly. The deregulation movement is now an historical footnote, just another interest group, and once in power they turned into socialists. Indeed, judging by the actions of the conservatives in power, and not the empty rhetoric that comes out of think tanks, the conservative movement has effectively turned the United States into a massive Socialist state, an appendage of Communist Russia, China and Venezuela.

To paraphrase Floyd Norris, we have become Marxists, but of the Groucho, not Karl, variety…

This is unbelievable:

The federal government is working on a sweeping series of programs that would represent perhaps the biggest intervention in financial markets since the 1930s, embracing the need for a comprehensive approach to the financial crisis after a series of ad hoc rescues.

At the center of the potential plan is a mechanism that would take bad assets off the balance sheets of financial companies, said people familiar with the matter, a device that echoes similar moves taken in past financial crises. The size of the entity could reach hundreds of billions of dollars, one person said.

In other words, folks spent years making billions upon billions of dollars on risky transactions, more money on the stock of companies that was artificially high based on those transactions, more money bundling all those transactions into more transactions, and made a killing, and when it turns out the whole thing is a big pile of shit, you and I get the god damned bill.

I do not ever want to hear another damned word about the free market. I don’t want to hear another thing about letting the market regulate itself. I don’t want to hear about the free flow of capital. I don’t want to hear about government getting out of our lives.

None of it. From superfunds to super-bailouts, I am tired of other people getting rich being irresponsible and then being told I have to pay to clean it up. I didn’t read one punitive aspect of this new plan. Not one punishment for the people who did this.

The bailout of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac will be sold and marketed as an effort to shore up the U.S. housing market. Maybe so. But it is mostly meant to shore up our damaged international financial standing, preserving leadership and making sure the U.S. Treasury Secretary doesn’t get tarred and feathered at the next G-8 meeting.

Along those lines, we see international stock markets cheer at the news; US housing prices not so much, I predict.

In the wake of the Freddie Mac/Fannie Mae bailout, Paul Krugman is pessimistic.

The current U.S. financial crisis bears a strong resemblance to the crisis that hit Japan at the end of the 1980s, and led to a decade-long slump that worried many American economists, including both Mr. Bernanke and yours truly. We wondered whether the same thing could take place here — and economists at the Fed devised strategies that were supposed to prevent that from happening. Above all, the response to a Japan-type financial crisis was supposed to involve a very aggressive combination of interest-rate cuts and fiscal stimulus, designed to prevent the crisis from spilling over into a major slump in the real economy.

When the current crisis hit, Mr. Bernanke was indeed very aggressive about cutting interest rates and pushing funds into the private sector. But despite his cuts, credit became tighter, not easier. And the fiscal stimulus was both too small and poorly targeted, largely because the Bush administration refused to consider any measure that couldn’t be labeled a tax cut.

As a result, as I suggested, the effort to contain the financial crisis seems to be failing. Asset prices are still falling, losses are still mounting, and the unemployment rate has just hit a five-year high. With each passing month, America is looking more and more Japanese.

So yes, the Fannie-Freddie rescue was a good thing. But it takes place in the context of a broader economic struggle — a struggle we seem to be losing.

As a rule I’m content to trust that my small band of readers will follow the excellent Dean Baker on their own (he’s the Beat the Press link on my Links list). But from time to time, I can’t resist reposting. This post recapitulates one of Baker’s themes, that the notion that corporate dividends are “double taxed” is fundamentally mistaken—or worse.

There is an old myth developed by rich people at some point in the distant past that paying taxes on dividends amounts to “double-taxation.” The argument is that profits are already taxed at the corporate level, so taxing money when it is paid out as dividends to shareholders is taxing the same profit a second time. Gregory Mankiw, a Harvard University professor and former top economist in the Bush administration, pushes this line in a column in the NYT.

The trick in this argument is that it ignores the enormous benefits that the government is granting by allowing a corporation to exist as a free standing legal entity. The most important of these advantages is limited liability. If a corporation produces dangerous products or emits dangerous substances that result in thousands of deaths, shareholders in the corporation cannot be held personally responsible for the damage. The corporation can go bankrupt, but beyond that point, all the shareholders are off the hook, the victims of the damage are just out of luck.

By granting corporate status, the government has allowed investors to shift risk to society as a whole. In exchange for this and other privileges of corporate status, the corporation must pay income tax on its earnings. We know that investors consider the benefits of corporate status to be worth the price in the form of the corporate income tax, because they voluntarily choose to form corporations. If investors did not consider the benefits of corporate status to outweigh the cost of the income tax, then they are free to form partnerships which are not subject to corporate income tax. In this way, the corporate income tax is a completely voluntary tax. Anyone can avoid the tax by investing in a partnership, or alternatively, any corporation can be restructured as a partnership.

The complaint about double taxation is an effort to get the benefits of corporate status for free. It is understandable that rich people would want to get benefits from the government at no cost, just like most of us would prefer not to pay our mortgage or electric bill. But, there is no reason for government to be handing out something of great value (corporate status) for free. If rich people don’t like the corporate income tax, they have a very simple way to avoid it — don’t invest in corporations. The problem is that the rich are just a bunch of whiners.

–Dean Baker

Dean Baker on one of his favorite subjects, the attribution of ideological motivations to political actors, quoted here mainly for its fine last line.

Frank-Dodd Bailouts: Arithmetic, Not Ideology

It is remarkable how often reporters/columnists feel the need to assert that political disputes are about ideological issues. Why do they feel the need to make assertions for which there is generally no evidence?

Politicians get elected by getting the support of individuals and groups with power. They don’t get elected by being political philosophers.Contrary to what Gretchen Morgenson (ordinarily a very good reporter) tells NYT readers, the battle over the Frank-Dodd bailout plans is not about ideology. The bills are crafted in ways that make them very friendly to banks. The banks get to decide which loans get put into the program. Presumably they don’t make this decision unless they think they will benefit from the bailout.

In addition, the appraisals on which the government’s guarantee price is set are based on sale prices, which may still be seriously inflated in the bubble markets. It would have been easy to avoid the problem of inflated appraisals by setting the guarantee price based on a multiple of rents. However, the supporters of these bills chose not to go this route.

At least some of the opposition to these bills is based on the view that giving more taxpayer dollars to banks should not be a higher priority than paying for health care, child care and other important needs. It is not clear what ideological issue is at stake here, since the ideology that we all should pay higher taxes to keep the banks rich has never been well articulated.

Emphasis mine.

James Hamilton speculates on the consequences of a US move to a gold standard in 2006.

What if we’d been on the gold standard?:

If the U.S. had decided to go back on the gold standard in 2006, where would we be today? That’s a question my friend Randy Parker recently asked me. Here’s how we both would answer.

…

In 1929, the U.S. was on a gold standard, with the exchange rate fixed at $20.67 per ounce of gold. Geopolitical insecurity and financial worries warranted an increase in the relative price of gold, which, with the dollar price of gold fixed, required a decline in the dollar price of most everything else. Speculators bet (correctly) that Britain would abandon the standard in 1931, but the U.S. fought against the speculation, with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York raising its discount rate from 1.5% to 3.5% in October 1931. This sharp increase in interest rates at a time of great financial turmoil succeeded in defending the parity with gold, but produced an economic disaster.

What’s the alternative, he asks, to abandoning the gold standard when staying on it requires raising interest rates in the face of a declining economy?

Or the other option would be to say, no, we really mean it this time, honest, we’re serious about this whole gold standard thing. So, we drive interest rates higher and watch the deflation mount. Outstanding debt that is denominated in dollars becomes more and more costly for people to repay, and we’d see a really impressive level of bankruptcies and business failures. The cycle would continue until the politicians who promised to stay on the gold standard are driven out of office and the deflation spiral could finally be ended by the new leaders choosing option 1 [abandoning the gold standard] after all.

I’m a month late posting this, but here we are. Kenneth Arrow (yes, that Kenneth Arrow) weighs in on the economics of mitigating climate change sooner rather than later. It’s particularly relevant as climate-change deniers shift from “it’s not happening” to “it’s too late (or too expensive) to do anything about it.”

The case for cutting emissions

Last fall, the UK issued a major government report on global climate change directed by Sir Nicholas Stern, a top-flight economist. The Stern Review Report on the Economics of Climate Change amounts to a call to action: It argues that huge future costs of global warming can be avoided by incurring relatively modest cost today.

Critics of the report don’t think serious action to limit carbon dioxide emissions is justified, because there remains substantial uncertainty about the extent of the costs of global climate change, and because these costs will be incurred far in the future.

However, I believe that Stern’s fundamental conclusion is justified: We are much better off reducing carbon dioxide emissions substantially than risking the consequences of failing to act, even if, unlike Stern, one heavily discounts uncertainty and the future.

Two factors differentiate global climate change from other environmental problems.

First, whereas most environmental insults — for example, water pollution, acid rain, or sulfur dioxide emissions — are mitigated promptly or in fairly short order when the source is cleaned up, emissions of carbon dioxide and other trace gases remain in the atmosphere for centuries. So reducing emissions today is very valuable to humanity in the distant future.

Second, the externality is truly global in scale, because greenhouse gases travel around the world in a few days. As a result, the nation-state and its subsidiaries, the typical loci for internalizing externalities, are limited in their remedial capacity. (However, since the US contributes about 25 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions, its own policy could make a large difference.) Thus, global climate change is a public “good” — as defined in economic terms — on an enormous scale.

…

A straightforward calculation shows that mitigation is better than business as usual — that is, the present value of the benefits exceeds the present value of the costs — for any social rate of time preference less than 8.5 percent. No estimate of the pure rate of time preference, even by those who believe in relatively strong discounting of the future, has ever approached 8.5 percent.These calculations indicate that, even with higher discounting, the Stern Review estimates of future benefits and costs imply that mitigation makes economic sense. These calculations rely on the report’s projected time profiles for benefits and its estimate of annual costs, about which there is much disagreement. Still, I believe there can be little serious argument about the importance of a policy aimed at avoiding major further increases in carbon dioxide emissions.