Following Dean Baker’s advice,

NYT Piece on Schumer/Democrats Ties to Wall Street

Anyone was wondering why the bank bailouts seem more designed to help Wall Street than the economy should read this piece.

—Dean Baker

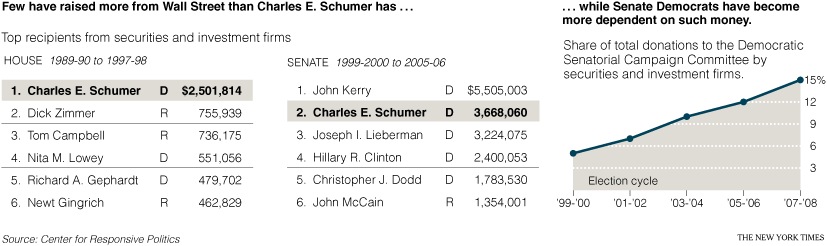

…we find this handy graphic:

“We are not going to rest until we change the rules, change the laws and make sure New York remains No. 1 for decades on into the future.”

— Senator Charles E. Schumer, referring to financial regulations, Jan. 22, 2007

…

While Mr. Schumer has taken some pro-consumer stances, his critics fault him for tilting too far toward Wall Street in balancing his responsibilities.“He is serving the parochial interest of a very small group of financial people, bankers, investment bankers, fund managers, private equity firms, rather than serving the general public,” said John C. Bogle, the founder and former chairman of the Vanguard Group, the giant mutual fund house. “It has hurt the American investor first and the average American taxpayer.”

…

To Christopher Cox, the Republican chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, the need for action was obvious in the spring of 2006.His agency, which would later be criticized for a 2004 ruling that let banks pile up debt, had grown deeply concerned about lack of oversight of the nation’s largest credit-rating agencies, like Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s Investors Service. Linchpins of the financial system, their ratings are vital to safeguarding investors by evaluating the risks of bonds and other debt. After the collapse of Enron and WorldCom, which had repeatedly been awarded favorable ratings, the agencies had agreed to meet voluntary standards.

But the S.E.C. concluded that those agreements were inadequate, so Mr. Cox urged Congress to give his agency oversight powers. “Without additional legislative authority, the S.E.C. will not be able to regulate in a thoroughgoing way,” he told the Senate banking committee at an April 2006 hearing.

The plan drew broad, bipartisan support on Capitol Hill. But executives at the credit-rating agencies soon began pressing Mr. Schumer and other allies in Congress to block the proposal or at least limit its reach, according to current and former employees.

“They knew Schumer would support them,” said one former Moody’s executive, who asked not to be named because he still works in the industry. “He was their go-to guy,” the executive said.

While the Manhattan-based agencies were not significant campaign donors to Mr. Schumer or the Senate campaign committee, their lobbyists and many of their clients were.

At that time, revenues for the agencies were skyrocketing. The housing market was robust, and Wall Street investment firms were paying the agencies to rate various mortgage-backed securities after first advising the firms — and also collecting fees — on how to package them to get high credit ratings.

It was an obvious conflict of interest, financial experts now say. Despite their high ratings, many of those securities, based on risky loans, would prove worthless, roiling markets and threatening financial institutions worldwide.

But Mr. Schumer argued that the companies voluntarily met requirements to eliminate such possible conflicts. He suggested that regulators simply encourage competition and disclosure of agencies’ ratings methods. There was perhaps no need for an intrusive new law, he said in the spring of 2006. “They’ve implemented their codes of conduct,” Mr. Schumer told Mr. Cox at a Senate hearing. “They’re making good-faith efforts.”

Mr. Schumer could not stop the legislation from passing, but he managed to get the measure amended so that it explicitly prohibited the S.E.C. from regulating the procedures and methods the agencies use to determine ratings.

…